The New New Criticism

A recent post here has garnered some attention from the internet, in particular, poet Joey De Jesus. He sent me a few messages on Twitter, reposted my article, and surprisingly, the two of us had a spirited–but in the end–friendly debate. We still disagree vehemently, but it might have been actually productive, which is odd because it took place on the internet. I would like to thank Joey for tweeting the article and posting it on Facebook, since after all, my goal is to get people talking about criticism, even if some of the conversation has reduced my argument to “white tears,” which, to my knowledge of the phrase, is an incorrect application. I don’t think it’s necessary to take others to task by name for their simplified engagement, as such arguments don’t actually state ideas or even offer criticism but instead, rely on the use of rhetorical devil-terms, designed to shut down argument rather than encourage it. With that said, however, I do want to get at the heart of what I began with “Kenneth Goldsmith and the Writ of Habeas Corpus”: Modern mainstream criticism has lost its way. Therefore, to Joey, because I hope you’re reading this, thanks.

So let me begin by saying I think I might take for granted the education I had as an undergrad. Many of today’s critics, who, as I’ve said before, are pretty highly educated, went to far more prestigous schools than me. But the thing I failed to recognize is that maybe those educations aren’t necessarily on the same page as mine. I don’t know to what extent many of today’s writers and poets learn about literary theory and the philosophical underpinnings behind a broad spectrum of critical approaches. It really depends on the program, and mine was very theory-based. (This is not to imply that your program was bad, dear reader, nor am I trying to talk down to those of you who bristle at the thought of theory. Presumably, we, and our respective programs, value and promote different ideas.) Furthermore, I’m well aware of the suspicious attitudes writers have voiced in the past about literary theory, as if it were some kind of slight of hand meant to distract, as if it undermines their authority as authors. (It does, and it should.) But for me, my undergrad experience has made my discovery and investigations of texts far more enriching, far more worthwhile–not to mention enhanced the thought I put into my own fiction. One text could, through the power of criticism, be seen through a multitude of lenses. We can see The Great Gatsby as a New Critic, a Freudian, a Feminist, a Structuralist, a New Historian, a Post-Colonialist, and one of my particular favorites, a Deconstructionist. However, I never felt comfortable identifying as any one type of critic. There were, after all, enormous benefits to each approach–as well as drawbacks. None, as I saw it, were perfect. Often, I would use the approach that I thought best fit that text. But my question is why these critical discourses are just that: discourses and not a discourse. Why can I not take these varying ideas and make them work together, rather than compete for authority?

And that’s exactly what I plan to do now.

The basis for any modern critical discipline has come from many of the tenets of New Criticism, in particular, the intentional fallacy and close reading. Just about every other critical approach relies on these two ideas. One, as stated in “The Intentional Fallacy” by Wimssatt and Monroe and later essentially expanded upon by Barthes as “the death of the author,” the author does not determine meaning. He or she has no greater claim on a text than anyone else. The author does not assign his or her own meaning and value. Two, the practice of close reading is meant to scrutinize each word, each mark of punctuation, every line break, every enjambment, every metaphor and simile, in order to determine how those choices determine the text’s meaning.

However, New Criticism does have its flaws.

It aims to discover the best interpretation. This, I would argue, is a mistake not only because it assumes there is one best interpretation but because that best interpretation focuses on what the text is actually about. This is where I start to differ with most critical theorists. I say that a text already has a specific meaning, that it is about that one specific idea (or specific ideas). That theme or meaning is fixed. Everything else about it is a quibble, because the rhetoric is clearly aimed at that goal, if it is a good, well-constructed text. We must recognize that at first. The other problem with New Criticism is its emphasis on “the text itself.” It dismisses valuable concepts in the rhetorical traingle like context, author, and audience for intent. Many of these points of the triangle have, thankfully, been reinstated and emphasized through the many different schools.

But, as I’ve said before, each new school of criticism only seems to acknowledge just one part of the triangle–except for Deconstruction which, at its worst, throws up its arms in an act of literary nihilism and says that meaning is “undecidable.” What would it look like if it acknowledged all parts of the rhetorical triangle, not just one? What if we married the princples of literary analysis and rhetorical analysis?

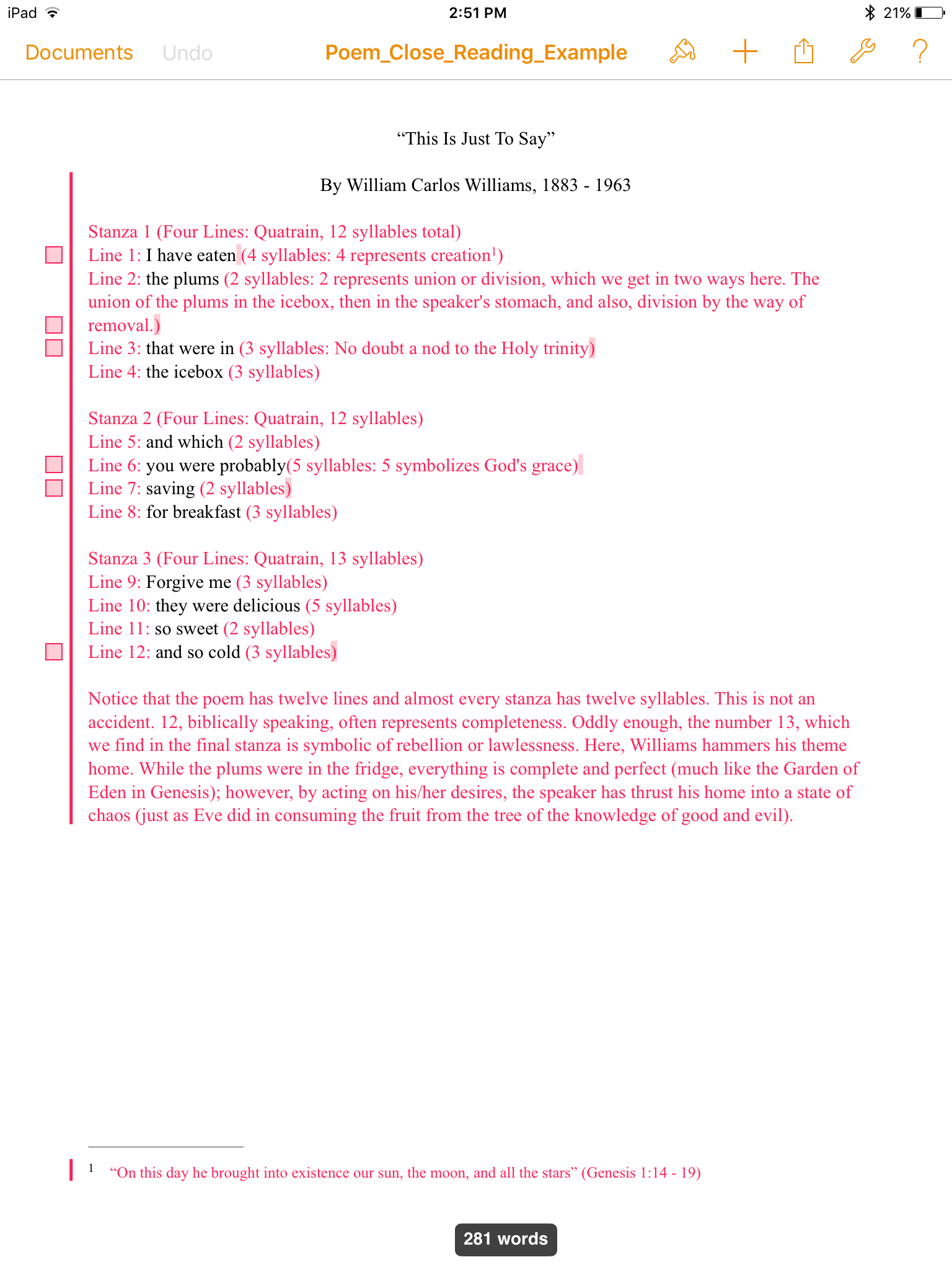

Let’s say we have a text, maybe “This is Just to Say” by William Carlos Williams. The first step should be to do an actual close reading, like this:

Post-It Note 1 (Line 1): This first line tells us a lot. First, we know that this is past tense, since it is “have eaten.” Second, this line is enjambed (it ends without punctuation in the middle of a sentence.). This suggests hesitation on the part of the speaker—the “I” of the poem. There is a clear sense of conflict in the speaker.

Post-It Note 2 (Line 2): Again, we have another enjambed line, putting special emphasis on the fruit itself. This choice seems very deliberate. The eating of forbidden fruit is a popular theme throughout Western literature (think Adam and Eve), and the speaker may be drawing that parallel.

Post-It Note 3 (Line 3): Line three, pauses again to emphasize the fruit’s non-existence and makes us consider its prior location as well.

Post-It Note 4 (Line 6): Here, the speaker introduces the second person, the “God” of the poem, who will, hopefully, forgive him/her.

Post-It Note 5 (Line 7): Notice that the line dwells on “saving,” which follows the line that introduces the “God” of the poem. Our speaker wants to be saved.

Post-It Note 6 (Line 12): This line which ends the poem may be a reference to the medieval view of hell. It was not a place of fire and brimstone, but a cold, cold home for sinners. The thinking was that the further away from God a person was, the further he/she was from God’s light.

This close reading observes the text itself and aims to decipher its “obvious” meaning. And since this is already a pretty simple poem, we know the theme is temptation. It is the tension between yielding and aversion. The privileged term here, seen through the speaker’s indulgence, is yielding, giving in. This, the poem tells us, is the better action. Of course, it is not that simple, since as we learn at the end that the act is both “sweet” and “cold,” signifying that has brought the speaker pleasure because it is delicous and pain because it has caused him or her guilt. The text is, therefore, in conflict with itself.

But in my close reading, I have also made historical and literary connections, which are not self-evident, not explicit. So the question is why? Clearly, I have a bias. I have imbued the text with what I see in it. I am actively constructing it in reader response. So we can say I have been influenced by my cultural landscape, particularly the hegemony of Christianity, as I draw connections between what I observe and with what I associate with what I observe.

And Williams has a bias too. His consciousness has also been shaped by the same cultural hegemony, corrupted by the institutional power of the Church, for the confessional nature of the poem highlights his own anixety over partaking in such a “sin.” Foucault, in his History of Sexuality, claims, “[O}ne does not confess without the presence or virtual presence of a partner who is not simply the interlocutor but the authority who requires confession.” The poem’s speaker’s pleasure may be blissful in the moment, but afterward, it leaves him or her empty and guilt-ridden, for which the only solution is confession. Such an attuitude concerning pleasure is contrary to the speaker’s (and by extention, Williams’s) own biological impulses, trapped in a Pavlovian cycle of pleasure always followed by pain.

Lastly, we must examine the context, the time and place in which the text was composed. Published in 1934, the poem is a product of its era, when, for the decade prior, there was the unbridled hedonism of Prohibition lurking beneath the surface of “dry” America, as all kinds of sexuality was celebrated by those who engaged in the counter-culture, but with the repeal of the 18th Amendment, returned puritanical denial and self-flagellation.

This approach, even as rushed, sloppy, and simplified as it is here, is what we need more of, an observation of all the points of the triangle, one that presents a more complete, complex, and thorough portrait of meaning, which hopefully gets even more complicated when we factor in things like race, gender, class, et cetera. Some may claim this is tedious–and I think it is–but it is also necessary. Criticism is designed to be just that.

Furthermore–and this should go without saying–this approach does not stake a claim on ultimate meaning. It is grounded in Cartesian uncertainity: It recognizes the subjectivity of experience. If anything, it is a Kierkegaardian leap of faith. But the important idea is that it demonstrates how the critic got to where they are. This idea is still very much in its infancy: There is more to be developed here, more to be scrutinized, more to be theorized, more to be tested, more to be investigated, more to be written and revised. But at least, it’s a start.