October 1, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

A recent post here has garnered some attention from the internet, in particular, poet Joey De Jesus. He sent me a few messages on Twitter, reposted my article, and surprisingly, the two of us had a spirited–but in the end–friendly debate. We still disagree vehemently, but it might have been actually productive, which is odd because it took place on the internet. I would like to thank Joey for tweeting the article and posting it on Facebook, since after all, my goal is to get people talking about criticism, even if some of the conversation has reduced my argument to “white tears,” which, to my knowledge of the phrase, is an incorrect application. I don’t think it’s necessary to take others to task by name for their simplified engagement, as such arguments don’t actually state ideas or even offer criticism but instead, rely on the use of rhetorical devil-terms, designed to shut down argument rather than encourage it. With that said, however, I do want to get at the heart of what I began with “Kenneth Goldsmith and the Writ of Habeas Corpus”: Modern mainstream criticism has lost its way. Therefore, to Joey, because I hope you’re reading this, thanks.

So let me begin by saying I think I might take for granted the education I had as an undergrad. Many of today’s critics, who, as I’ve said before, are pretty highly educated, went to far more prestigous schools than me. But the thing I failed to recognize is that maybe those educations aren’t necessarily on the same page as mine. I don’t know to what extent many of today’s writers and poets learn about literary theory and the philosophical underpinnings behind a broad spectrum of critical approaches. It really depends on the program, and mine was very theory-based. (This is not to imply that your program was bad, dear reader, nor am I trying to talk down to those of you who bristle at the thought of theory. Presumably, we, and our respective programs, value and promote different ideas.) Furthermore, I’m well aware of the suspicious attitudes writers have voiced in the past about literary theory, as if it were some kind of slight of hand meant to distract, as if it undermines their authority as authors. (It does, and it should.) But for me, my undergrad experience has made my discovery and investigations of texts far more enriching, far more worthwhile–not to mention enhanced the thought I put into my own fiction. One text could, through the power of criticism, be seen through a multitude of lenses. We can see The Great Gatsby as a New Critic, a Freudian, a Feminist, a Structuralist, a New Historian, a Post-Colonialist, and one of my particular favorites, a Deconstructionist. However, I never felt comfortable identifying as any one type of critic. There were, after all, enormous benefits to each approach–as well as drawbacks. None, as I saw it, were perfect. Often, I would use the approach that I thought best fit that text. But my question is why these critical discourses are just that: discourses and not a discourse. Why can I not take these varying ideas and make them work together, rather than compete for authority?

And that’s exactly what I plan to do now.

The basis for any modern critical discipline has come from many of the tenets of New Criticism, in particular, the intentional fallacy and close reading. Just about every other critical approach relies on these two ideas. One, as stated in “The Intentional Fallacy” by Wimssatt and Monroe and later essentially expanded upon by Barthes as “the death of the author,” the author does not determine meaning. He or she has no greater claim on a text than anyone else. The author does not assign his or her own meaning and value. Two, the practice of close reading is meant to scrutinize each word, each mark of punctuation, every line break, every enjambment, every metaphor and simile, in order to determine how those choices determine the text’s meaning.

However, New Criticism does have its flaws.

It aims to discover the best interpretation. This, I would argue, is a mistake not only because it assumes there is one best interpretation but because that best interpretation focuses on what the text is actually about. This is where I start to differ with most critical theorists. I say that a text already has a specific meaning, that it is about that one specific idea (or specific ideas). That theme or meaning is fixed. Everything else about it is a quibble, because the rhetoric is clearly aimed at that goal, if it is a good, well-constructed text. We must recognize that at first. The other problem with New Criticism is its emphasis on “the text itself.” It dismisses valuable concepts in the rhetorical traingle like context, author, and audience for intent. Many of these points of the triangle have, thankfully, been reinstated and emphasized through the many different schools.

But, as I’ve said before, each new school of criticism only seems to acknowledge just one part of the triangle–except for Deconstruction which, at its worst, throws up its arms in an act of literary nihilism and says that meaning is “undecidable.” What would it look like if it acknowledged all parts of the rhetorical triangle, not just one? What if we married the princples of literary analysis and rhetorical analysis?

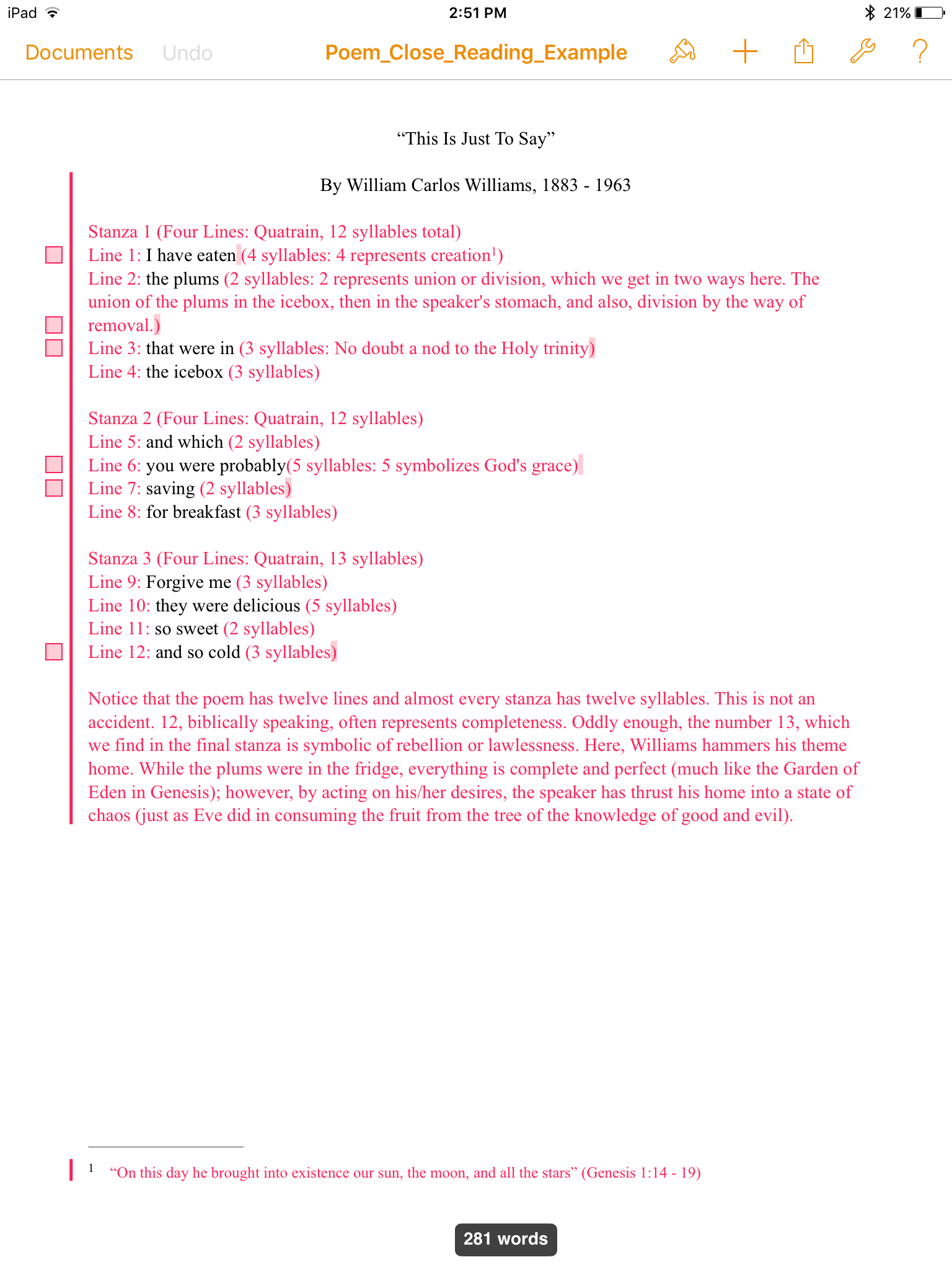

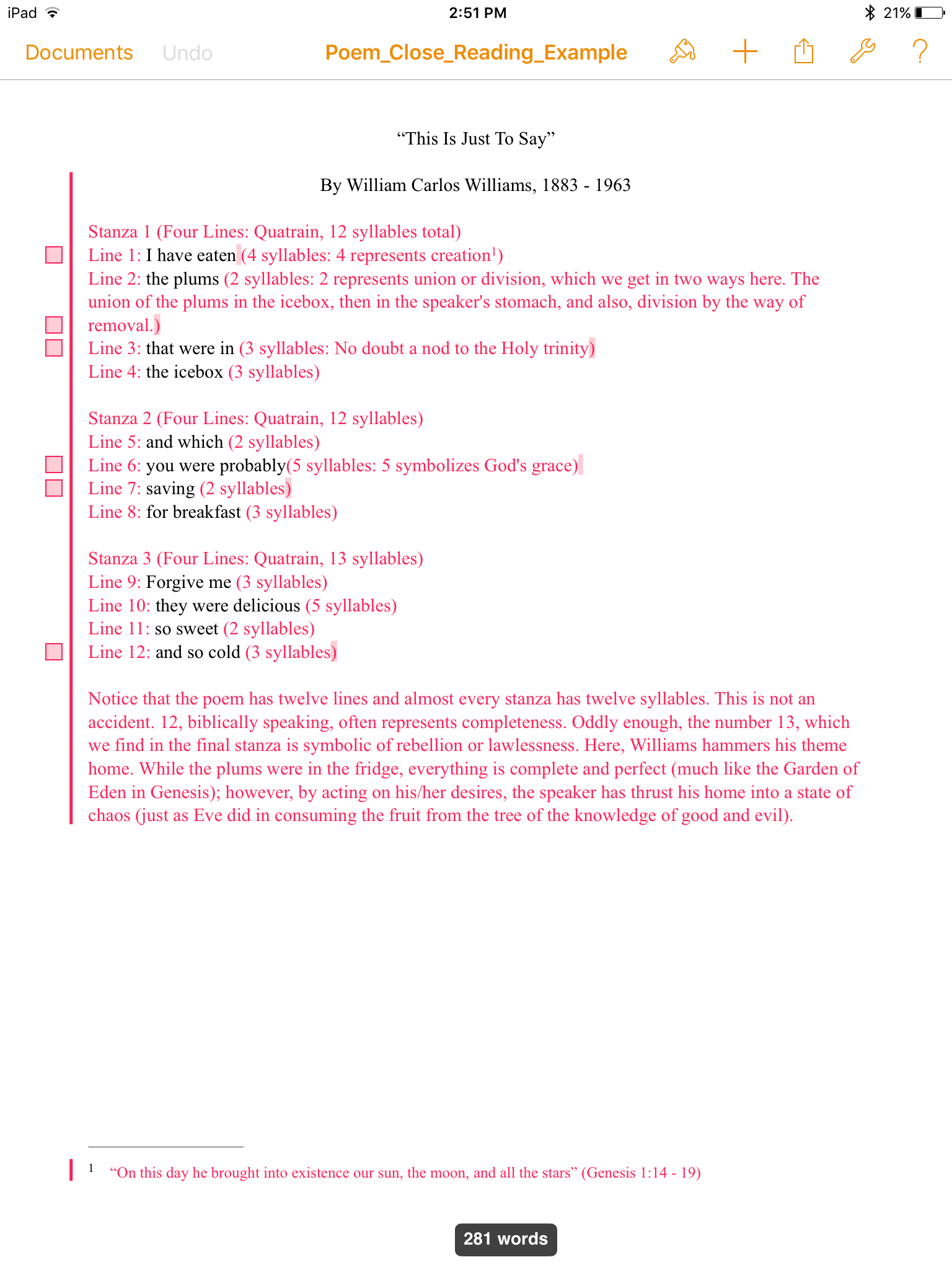

Let’s say we have a text, maybe “This is Just to Say” by William Carlos Williams. The first step should be to do an actual close reading, like this:

Post-It Note 1 (Line 1): This first line tells us a lot. First, we know that this is past tense, since it is “have eaten.” Second, this line is enjambed (it ends without punctuation in the middle of a sentence.). This suggests hesitation on the part of the speaker—the “I” of the poem. There is a clear sense of conflict in the speaker.

Post-It Note 2 (Line 2): Again, we have another enjambed line, putting special emphasis on the fruit itself. This choice seems very deliberate. The eating of forbidden fruit is a popular theme throughout Western literature (think Adam and Eve), and the speaker may be drawing that parallel.

Post-It Note 3 (Line 3): Line three, pauses again to emphasize the fruit’s non-existence and makes us consider its prior location as well.

Post-It Note 4 (Line 6): Here, the speaker introduces the second person, the “God” of the poem, who will, hopefully, forgive him/her.

Post-It Note 5 (Line 7): Notice that the line dwells on “saving,” which follows the line that introduces the “God” of the poem. Our speaker wants to be saved.

Post-It Note 6 (Line 12): This line which ends the poem may be a reference to the medieval view of hell. It was not a place of fire and brimstone, but a cold, cold home for sinners. The thinking was that the further away from God a person was, the further he/she was from God’s light.

This close reading observes the text itself and aims to decipher its “obvious” meaning. And since this is already a pretty simple poem, we know the theme is temptation. It is the tension between yielding and aversion. The privileged term here, seen through the speaker’s indulgence, is yielding, giving in. This, the poem tells us, is the better action. Of course, it is not that simple, since as we learn at the end that the act is both “sweet” and “cold,” signifying that has brought the speaker pleasure because it is delicous and pain because it has caused him or her guilt. The text is, therefore, in conflict with itself.

But in my close reading, I have also made historical and literary connections, which are not self-evident, not explicit. So the question is why? Clearly, I have a bias. I have imbued the text with what I see in it. I am actively constructing it in reader response. So we can say I have been influenced by my cultural landscape, particularly the hegemony of Christianity, as I draw connections between what I observe and with what I associate with what I observe.

And Williams has a bias too. His consciousness has also been shaped by the same cultural hegemony, corrupted by the institutional power of the Church, for the confessional nature of the poem highlights his own anixety over partaking in such a “sin.” Foucault, in his History of Sexuality, claims, “[O}ne does not confess without the presence or virtual presence of a partner who is not simply the interlocutor but the authority who requires confession.” The poem’s speaker’s pleasure may be blissful in the moment, but afterward, it leaves him or her empty and guilt-ridden, for which the only solution is confession. Such an attuitude concerning pleasure is contrary to the speaker’s (and by extention, Williams’s) own biological impulses, trapped in a Pavlovian cycle of pleasure always followed by pain.

Lastly, we must examine the context, the time and place in which the text was composed. Published in 1934, the poem is a product of its era, when, for the decade prior, there was the unbridled hedonism of Prohibition lurking beneath the surface of “dry” America, as all kinds of sexuality was celebrated by those who engaged in the counter-culture, but with the repeal of the 18th Amendment, returned puritanical denial and self-flagellation.

This approach, even as rushed, sloppy, and simplified as it is here, is what we need more of, an observation of all the points of the triangle, one that presents a more complete, complex, and thorough portrait of meaning, which hopefully gets even more complicated when we factor in things like race, gender, class, et cetera. Some may claim this is tedious–and I think it is–but it is also necessary. Criticism is designed to be just that.

Furthermore–and this should go without saying–this approach does not stake a claim on ultimate meaning. It is grounded in Cartesian uncertainity: It recognizes the subjectivity of experience. If anything, it is a Kierkegaardian leap of faith. But the important idea is that it demonstrates how the critic got to where they are. This idea is still very much in its infancy: There is more to be developed here, more to be scrutinized, more to be theorized, more to be tested, more to be investigated, more to be written and revised. But at least, it’s a start.

September 29, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

I know I’m late to this party, but The New Yorker just ran a profile on Kenneth Goldsmith, which many have stayed silent on–and when they have been willing to talk, it’s been outright hostile. The National Book Critics Circle Board retweeted one person’s plea to the editor of Poetry Magazine to retweet the article, which was followed by responses like, “So the lesson here is be a lazy racist and get a lot of press?” and “trash.” One response I found particularly disheartening came from Justin Daugherty, founder of Sundog Lit and editor of Cartridge Lit, who wrote in a now deleted tweet, “KG [Kenneth Goldsmith] is a garbage human.” Now maybe Daugherty and others have had a chance to meet Goldsmith in person and found him to be “trash” and “garbage.” It’s well within the realm of possibilty, but I think, more so, Daugherty is referring to Goldsmith’s poem “The Body of Michael Brown,” which remixes the autopsy report of the young man shot by police whose death served as a catlyst for activism and riots in Ferguson, Missouri. While I think there’s an argument to be made that such an act was “too soon,” social media and the literary blogosphere took a different approach: a shitstorm of moral outrage and indignation. Most arguments against Goldsmith’s performance, from Joey de Jesus’s essay at Apogee to Flavorwire, focused on the act itself, rather than the actual text. And you’re probably wondering: Where can I read/see this? The short answer, ironically during banned books week, is you can’t. And just about none of Goldsmith’s critics have had the chance either. So how, exactly, have so many determined so much based on so little? Don’t we need a text to criticize, to scruntize, to determine whether it was racist or not, as so many have claimed? Shouldn’t analysis and interpretation be based on textual evidence? Probably what I find most distressing is that these writers and editors, who have uniformly condemned Goldsmith and his poem, should know better. They are, first and foremost, artists, and we have all seen plenty of challenges to our freedom in the past and present. But also these are men and women with MFAs and PhDs from the best schools in the country, where the faculty are active scholars who have faced the rigors of peer review, who, presumably, expect the same focused, logical, detailed, thorough analyses from their students. So how, then, have things gone so wrong?

#

In rhetoric and composition studies, we often talk about the rhetorical triangle, which is the connection between the writer, the audience, and the message. This, of course, is framed within a certain context. Most schools of literary criticism place greater value on one of these facets. The New Critic emphasizes intent. The Reader Response Critic focuses on audience. The Freudian psychoanalyzes the author. The New Historian privileges the context. None of these, I would say, are any more useful than the other. In fact, this is one criticism’s biggest flaws–especially as of late. These things, individually, don’t bring us any closer to meaning. They need to be recognized in concert with one another.

Unfortunately, things have only gotten worse.

Due to the increasing influence of identity politics, both the author and the context are all that matter. The text, it seems, has become irrelevant. We don’t care what was actually on the page. That should worry any serious artist or critic. As T. S. Eliot once wrote, “[A] critic must have a very highly developed sense of fact.” But this current trend ignores or disregards evidence which may be contrary to the critic’s conclusions, which often means the diction choices, the form, the imagery, the structure–all of it has been reduced to some irrelevant detail. Critics claim that a text is a vehicle through which our gender roles, class system, and structural inequalities are reinforced rather than challenged. When–and why the hell did this happen? To that, I don’t really have an answer, but I can say that such a trend should be unnerving to any artist, regardless of his or her politics.

First of all, what artist is a complete shill for society? I couldn’t give a fuck about how good or bad he or she may be: Artists are free-thinkers. We’re independent. We have empathy, logic, humanity. We recognize the beauty and benefits of all things–even those we hate. That’s our job. Otherwise, we’re not looking at a poem or a story or a painting, but a didactic piece of shit that our audience will find more alienating than enlightening. Isn’t it OK to be OK with some of the ways that society operates? (This is not a tacit endorsement of racism or sexism or anything of the like, but more so a way to say I don’t entirely mind free markets as long as they’re regulated pretty heavily.) Secondly, I’m not fond of the deterministic philosophy which underpins much of this approach. Whether it’s Tropes vs. Women or an article in the LA Review of Books, the assumption is that society is racist, sexist, and heterosexist, even when it’s actively fighting against it. They preach to us that it is inescapable, but they, of course, have the power to point it out. They are the Ones. They can see the Matrix that you and I can’t. Only they can see, as bell hooks puts it, “the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” And while I respect hooks as a rhetorican, I find her conclusion suspect. Let me say, there are absolutely inequalities that exist, problems that exist, but the suggested cause is far too simplistic, as, much like today’s literary criticism, it ignores a lot of contradictory evidence in favor of the ancedotal. Worse still, the solutions are far, far too vague (reform? revolution? change behaviors? change literature?). These issues will not be solved by preachy art: They are solved at the ballot box. (If you became a critic to “make a difference,” try running for office instead.) Art isn’t overly concerned with the right now: It uses the specific to tell us something about the universal.

#

So where do we go from here? I think we need to return to the “scientific” approach proposed by Ransom all those years ago in “Criticism Inc.“–with some caveats, of course. We have to do a thorough close reading of a text in order to discover the intent, but we also need to stress the other points of the rhetorical triangle as well. The message is important, but so is the ways a text undermines its own theme, the constant battle of binary opposites. We, too, must recognize the biases of the reader and the author and the time and circumstances under which it was produced just as we recognize the importance of “the text itself.”

#

So I’d like to leave you with a lie I tell my literature students every semester. I say: In this class, there are no wrong answers. I know that’s not true, but I say it because I don’t want them to be afraid of analysis, to fear interpretation. However, I realize there are “wrong” answers, invalid answers. You can’t just pull shit out of your ass and say it is: You must demonstrate it through a preponderance of textual evidence. This is the cardinal rule of criticism. Yet as my students’s first paper (on poetry no less) approaches, I let them in on this little distinction between valid and invalid arguments. It would appear that many of Goldsmith’s critics skipped that day of school.

September 6, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

For a while now, this blog has been promoted as a place that talks about academic issues, the nuts and bolts of writing, and the art of games. One of those, of course, has been much neglected. I might make a passing mention of a game here and there, but overall, I haven’t really taken the time to talk about it at length–which is a shame. Now, however, I intend to rectify this oversight with some musings on an approach to games criticism.

#GamerGate has been widely misunderstood as a whole, in much the same way we view any leaderless grassroots movement. It’s pretty hard to talk about something so amporphous and divergent. Some people seem to think it’s about ethics in games journalism. Others say it’s about the caustic influence of identity politics. Others say it’s an excuse for harassment. In many ways, all of these things are valid, I think, but it also demonstrates how much we like hearing ourselves talk. Whatever the movement represents to you is probably predetermined, and there’s likely no way to sway you to another opinion. Sadly, most of these topics are relegated to different spheres. The people who face harassment in and around the industry, of which there are many, shed light on a serious topic, one we should all be committed against. Of course, that doesn’t mean we should ignore ethical breaches or halt discussions about how to assess art. The people who bemoan the invasion of identity politics have legimate claims too, issues we have to consider, but it doesn’t mean they should blithely brush aside the discrimination people face. Instead of actually engaging in these peripheral conversations, most of the time, these true believers continue to preach from their megaphones and silence any dissent.

In truth, there are a lot competing ideas, an argument without focus. Is there sexism in games and the industry? Most likely. Is it annoying to read a review that epouses a philosophy and provides little analysis and cherry-picked evidence without assessing whether a game is “fun” or not? Sure. Are journalists, and this doesn’t even just apply to games journalism, a little too close to their subjects? Absolutely. These things are largely hard to disprove or refute. They just kind of are. However, much like Occupy Wall Street, I don’t think the conversation has been entirely productive. It’s a lot of self-pleasure, appealing solely to one’s own audience: mental masturbation. Frankly, that doesn’t interest me. Instead, I’d rather look at solutions to definitive problems, and since my background is dedicated to the creation and appreciation of art, it only makes sense to talk about games criticism at large.

It’d probably best to start with an admission: Most mainstream criticism, of all art, is garbage. It’s not about careful consideration, thorough analysis, and nuance. In most cases, the critics we find in newspapers and blogs–those who critique our books, our films, our video games–don’t spend a lot of time crafting their argument. They don’t mine every available piece of evidence. They don’t look at a text as whole. They don’t qualify their statements or follow through on the logic of their thinking. As Allan Bloom puts it in The Closing of The American Mind, “[T]here is no text, only interpretation.” In other words, they ignore the very thing under scrunity. They don’t care what it actually says, but instead, they care what they believe it to say. Of course, mainstream critics have deadlines and numbers to meet. It is not, after all, academia, where those things aren’t as important. What I’m trying to say is that contemporary critics react emotionally. They feel their opinions to be true.

And that, to me, is the biggest problem. If we aren’t thorough, if we don’t apply the skill of close reading, how can we really make any kind of aesthetic judgement?

Most games critics don’t seem to have a theoretical basis for their, admittedly, abitrary scores. They say the graphics are great or that the story drew them in. The truth is, I could give a fuck how it made you feel. What I want to know is why. I want evidence. This, again, isn’t entirely their fault. Now, more than ever, people flip shit if there’s even the suggestion of a spoiler, as if the fun of a piece of art is the mystery of what happens next. This, as I’ve said in the past, is a load of bullshit. It doesn’t ruin the experience: It enhances it. When we know what to look for going in, it makes appreciating the craft that much more satisfying. That does not mean that we should expect only to find what the critic has found. If anything, the real disaster would be to allow one reading to bias our own reading, but such a matter is of an individual’s own sense of discovery, their own inability to think for themselves.

So the question arises: How do we assess this artform? What criteria should we use to choose play or not play?

The answer is largely subjective, as we all have different approaches to art, but I think we can, thanks to New Criticism, lay a foundation. Every game is about something, a central tension, an idea, a philosophy its trying to express. Our job is to discover it, which we often do quite quickly. In a mere matter of moments, we can articulate the theme of just about anything. Yet if you were ask us how we had made such a realization, we would presumably say it just is. This, to me, is the first mistake. We need to actually show that theme and how it’s communicated, which means a thorough, careful reading based on a preponderance of evidence. Just as a math teacher asks us to show our work, so must we. The theme should inform every facet of the text: Its setting, its graphics, its design, its gameplay, its characters, its structure. If we talk explicitly, specifically about these elements, then we can form an argument and make our case.

To an extent, there are already a few publications who take this approach, like IGN or The Completionist. However, most reviewers who take such an approach fail to deliever compelling and in-depth evidence to their claims. Again, the text just simply is.

There are others out there, Polygon and Kotaku in particular, who have started to inject moral studies into their reviews. (Polygon’s review of Bayonetta 2 comes to mind.) As an academic, this isn’t all that egregious to me. Feminist, post-colonial, queer, and Marxist criticisms are not exactly new. However, I can understand the anger consumers feel coming into a review expecting to learn whether it’s fun or not and then hearing someone talk about gender roles and objectification. “What does it have to do with the game?” they ask. Most gamers aren’t aware of the jargon of cloistered academics. That’s not to say we shouldn’t practice these approaches or that they can’t serve as a guide for our criticism (it is very easy to marry that framework with New Criticism), but more so that we, as consumers, should know what we’re getting into.

So let’s get to the point here: Games publications should announce their critical lens. I want to know where you’re coming from. How are you looking at a game? What are your criteria? What do you privilege in your assessment? Most editors give some lip-service to these ideas, but none really ever declare a manifesto, a reason for their existence. Presumably, they assume we should learn this by reading the magazine. It’s a nice thought, but I think it’s a bit unreasonable. There’s so much to learn out there, so many opinions. Can I really read through every article you’ve published to get a feel for your publication just to decide if it’s for me? And what if the editor changes and hence their vision? That’s a lot to expect from anyone.

In short, there are two problems with games criticism as I see it. One, when dealing with a specific text, reviewers/critics fail to give specific examples to illustrate their claims and/or investigate their own criteria for what makes a game worth playing, which is why consumers resent the injection of moral studies in what they believe to be an objective analysis. Two, games publications don’t really announce their editorial vision. Though I don’t think these solutions will ever take a hold any time soon, I still hope that at least one publication comes along who adopts such practices. Maybe if such things were commonplace, we’d see a little less anger in the comments and a little more rational, intelligent debate.

August 10, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

Lately, I have heard a lot about ideas such as cultural appropriation and cultural exchange, ideas of privilege and oppression, ideas, which, ultimately create a quandary for the artist. Of particular note, has been the increased calls for diversity, both behind the art and in the thing itself. These goals, I believe, are admirable and well within reason. It is largely benign, of neither insult nor disfigurement to American art at large; instead, it is to our shared benefit. We should have a plethora of unique and boisterous voices to admire. Good art is always worth striving for. However, there seems to be strain of these criticisms that seems ill-defined at best, an uncertainty, an inability to articulate exactly what the critic wants. The closest I have to a definitive statement comes from J. A. Micheline’s “Creating Responsibly: Comics Has A Race Problem,” where the author states: “Creating responsibly means looking at how your work may impact people with less structural power than you, looking at whether it reifies larger societal problems in its narrative contents or just by existing at all.” There are a couple of ideas here that I take issue with, ones that don’t necessarily mesh with my ideals of the artist.

Hegel wrote that “art is the sensuous presentation of ideas.” Nowhere is the suggestion that art comes attached with responsibilities. I’m not saying that art doesn’t have the power to shape ideas, but more so, there is often a carefully considered and carefully crafted idea at the heart of every work of art. That overarching theme is given precedence and whatever other points a critic discerns in a work fails to recognize the text’s core. In other words, how can we present evidence of irresponsibility of ideas that are not in play?

This, no doubt, branches out of the structuralist and post-structuralist concepts of binary opposition, and most of all, deconstruction’s emphasis on hierarchical binaries. I no doubt concede that such things exist in every text: love/hate, black/white, masculine/feminine, et cetera. However, the great flaw in this reasoning is that these binaries, even when they arise unconsciously, conclusively state a preference in the whole. Such thinking is a mistake. If we reason that such binary hierarchies exist, why should we conclude that they are unchanging and fixed? Such an idea is impossible, regardless how much or how little the artist invests in their creation. Let’s take a look at a sentence–a tweet, in fact from Roxane Gay–in order to make such generalities concrete:

I’m personally going to start wearing a lion costume when I leave my house so if I get shot, people will care.

We will ignore the I of this statement as it is unnecessary in order to make this point. We have to unpack the binaries at play. First, we note the distinctions in life/death, animals/humans (and also humans/animals). These binaries exist solely inside this shell, yet, if we consider this as a part of a much larger endeavor, we are likely to find contradictory binaries in other sentences. When exactly can we decide the author has concluded? How can we determine the author’s point? Can we ever decide? Now think of applying such an act to a text of 60,000, 80,000, 100,000 words. There’s no doubt it is possible. Yet, should we sit there and count any and every binary that privileges one of the terms? Would that move us any closer to a coherent and definitive message? I find it unlikely.

Of course, I’m not advocating for a return to the principles of New Criticism nor I am saying that post-modern philosophy and gender/race/queer theory have no place in the literary discourse, but to simplify a text, to ignore its argument, seems inherently dishonest. Critics are searching for validation of their own biases, a want to see what they see in society whether real or imagined. This is by no means new, as Phyllis Rackin notes in her book Shakespeare and Women, “One of the most influential modern readings of As You Like It, for instance, Louis Adrian Montrose’s 1981 article, ‘The Place of a Brother,’ proposed to reverse the then prevailing view of the play by arguing that ‘what happens to Orlando at home is not Shakespeare’ contrivance to get him into the forest; what happens to Orlando in the forest is Shakespeare’s contrivance to remedy what has happened to him at home’ (Montrose 1981: 29). Just as Oliver has displaced Orlando…Montrose’s reading displaces Rosalind from her place as the play’s protagonist….” Rackin’s point is clear: If you go searching for your pet issue, you’re bound to find it.

#

I am not fond of polemical statements nor do I want to approach this topic in a slippery-slope fashion as it simplifies a large and complex issue which is too often simplified to fit the writer’s implicit biases. In order to explore thorny or shifting targets such as these, we need to strip away whatever artifice clouds our judgement and consider the assumptions present therein. Unfortunately, most of the discourse has been narrowly focused, boiling down to little more than a sustained shouting contest, a question of who can claim the high ground, who can label the other a racist first. This is not conducive to any dialogue and only serves to make one dig in their trenches more deeply. It is distressing to say the least.

One of the assumptions most critics make goes to the pervasiveness of power, that power is, as Foucault puts it, everywhere, that there is no one institution responsible for oppression, no one figure to point to, but instead, it is diffused and inherent in society. Of course, Foucault’s definition of power is far from definitive and impossible to pin-down. Are we merely subject to the dominance of some cultural hegemony, some ethereal control that dictates without center as some suggest? This, it seems to me, only delegitimizes the individual. Foucault suggests that the subject is an after-effect of power; however, power is not a wave that merely washes over us. It is a constant struggle for supremacy. Imagine it on the smallest scale possible: the interaction of two. Even when one achieves mastery over the other, the subordinate does not relinquish his identity. These two figures will always be two, independent to some degree. The subordinate is relinquishing control not by coercion but by choice. Should the subordinate resist, and he does so simply through being, the balance of power shifts however slightly.

Existence is not a matter of “cogito ergo sum,” but a matter of opposition, that as long as there is an other, we exist.

#

Many people have made the distinction between cultural exchange and cultural appropriation, that the former is a matter of fair and free trade across cultures while the latter is an imposition, a theft of cultural symbols used without respect. While this sounds reasonable, the exchange is impossible.

There is no possibility of fair and equal trade: One will always have power over another.

We assume that American culture is some definable entity, that there is some overall unity to it, but just as deconstructionists demonstrated the unstable undecidability of a text, a culture too is largely undecidable. A culture is not some homogenous mass, but a series of oppositions at play, vying for influence.

We can use myself as an example. Of the categories to which I subscribe or am I assigned, I am a male, cis, white, American, Italian-American, liberal, a writer, an academic, a thinker, a lover of rock n roll, and so on. Each of these cultures are in opposition to something else: male/female, cis/trans, white/black, white/asian, white/hispanic, et cetera. These individual categories form communities based on shared commonalities, but to suggest that these segregating categories can form a cultural default or mainstream is deceptive. Each sphere is distinct from the other, a vast network of connections that ties one individual to a host of others based on one facet. Yet this shared sphere does not create a unified whole. There is no one prevailing paradigm. It is irreducibly complex.

So what’s the point here?

Cultural appropriation, if such a thing exists, is inevitable.

#

It should go without saying, but these ideas of oppression and power are ultimately relative. Depending on what community you venture into and your privilege inside it, you will find yourself in one of these two positions—always. America is as much a text as a novel or any other piece of art. We can count up our spheres of influence, those places we are powerful and those places we are powerless and come no closer to overall meaning.

This is not a call to throw up our hands in nihilistic despair for the artist. The artist would be wise to remember their own power, their ability to draw the world uniquely as they see it. If an artist has an responsibility at all, it is not to worry what part of the binary they are or are not privileging, what hierarchy they summon into being. Someone will always be outraged, oppressed, angered as long as they are looking for something to rage about, regardless of whether it is communicated consciously or not.

Freudian criticism often looks at the things that the author represses in the text, the thoughts and emotions that the author is unwilling to admit explicitly. When asked to give evidence, the critic often claims that the evidence does not need to be demonstrated because it cannot be found: It is somehow hidden. And it is this vein, that sadly, has infected our current approach to texts. We co-opt a text for our own biases, to express what the critic can project onto them, rather than what the work itself describes. We look for any example which might fit our goal and consider it representative of the whole. That is cherry-picking at its most obvious, and an error we should all strive to avoid.

We tend to forget that there are bad texts available to us, that do absolutely advocate the type of propaganda that critics infer in works that approach their subjects with care and grace. How can we scrutinize The Sun Also Rises as antisemitic, as heterosexist, as misogynist when we have books like The Turner Diaries that clearly are? How can we damn Shakespeare for living in a certain era? How can we cast out great works which recognize the complexity of existence and ignore those which undoubtedly make us uneasy?

To the point, we are more enamored by the implicit over the explicit. The central argument of a text is what deserves our attention, how it is made and whether it is successful. We cannot presume to know the tension of other binaries as that text is still being written, constantly shifting, unending in its fluidity.

#

It is easy to make demands on the artist. Anyone can do it. Criticism is one of the few professions that does not require any previous knowledge or qualification. It is, at its heart, an act of determining meaning, and many, I would argue, have been unsuccessful. The hard part is creating meaning. And to those who make some great claim on what art should or should not do, my advice is simple: Shut up and do it yourself, because, by all means, if it’s that easy, demonstrate it.