October 1, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

A recent post here has garnered some attention from the internet, in particular, poet Joey De Jesus. He sent me a few messages on Twitter, reposted my article, and surprisingly, the two of us had a spirited–but in the end–friendly debate. We still disagree vehemently, but it might have been actually productive, which is odd because it took place on the internet. I would like to thank Joey for tweeting the article and posting it on Facebook, since after all, my goal is to get people talking about criticism, even if some of the conversation has reduced my argument to “white tears,” which, to my knowledge of the phrase, is an incorrect application. I don’t think it’s necessary to take others to task by name for their simplified engagement, as such arguments don’t actually state ideas or even offer criticism but instead, rely on the use of rhetorical devil-terms, designed to shut down argument rather than encourage it. With that said, however, I do want to get at the heart of what I began with “Kenneth Goldsmith and the Writ of Habeas Corpus”: Modern mainstream criticism has lost its way. Therefore, to Joey, because I hope you’re reading this, thanks.

So let me begin by saying I think I might take for granted the education I had as an undergrad. Many of today’s critics, who, as I’ve said before, are pretty highly educated, went to far more prestigous schools than me. But the thing I failed to recognize is that maybe those educations aren’t necessarily on the same page as mine. I don’t know to what extent many of today’s writers and poets learn about literary theory and the philosophical underpinnings behind a broad spectrum of critical approaches. It really depends on the program, and mine was very theory-based. (This is not to imply that your program was bad, dear reader, nor am I trying to talk down to those of you who bristle at the thought of theory. Presumably, we, and our respective programs, value and promote different ideas.) Furthermore, I’m well aware of the suspicious attitudes writers have voiced in the past about literary theory, as if it were some kind of slight of hand meant to distract, as if it undermines their authority as authors. (It does, and it should.) But for me, my undergrad experience has made my discovery and investigations of texts far more enriching, far more worthwhile–not to mention enhanced the thought I put into my own fiction. One text could, through the power of criticism, be seen through a multitude of lenses. We can see The Great Gatsby as a New Critic, a Freudian, a Feminist, a Structuralist, a New Historian, a Post-Colonialist, and one of my particular favorites, a Deconstructionist. However, I never felt comfortable identifying as any one type of critic. There were, after all, enormous benefits to each approach–as well as drawbacks. None, as I saw it, were perfect. Often, I would use the approach that I thought best fit that text. But my question is why these critical discourses are just that: discourses and not a discourse. Why can I not take these varying ideas and make them work together, rather than compete for authority?

And that’s exactly what I plan to do now.

The basis for any modern critical discipline has come from many of the tenets of New Criticism, in particular, the intentional fallacy and close reading. Just about every other critical approach relies on these two ideas. One, as stated in “The Intentional Fallacy” by Wimssatt and Monroe and later essentially expanded upon by Barthes as “the death of the author,” the author does not determine meaning. He or she has no greater claim on a text than anyone else. The author does not assign his or her own meaning and value. Two, the practice of close reading is meant to scrutinize each word, each mark of punctuation, every line break, every enjambment, every metaphor and simile, in order to determine how those choices determine the text’s meaning.

However, New Criticism does have its flaws.

It aims to discover the best interpretation. This, I would argue, is a mistake not only because it assumes there is one best interpretation but because that best interpretation focuses on what the text is actually about. This is where I start to differ with most critical theorists. I say that a text already has a specific meaning, that it is about that one specific idea (or specific ideas). That theme or meaning is fixed. Everything else about it is a quibble, because the rhetoric is clearly aimed at that goal, if it is a good, well-constructed text. We must recognize that at first. The other problem with New Criticism is its emphasis on “the text itself.” It dismisses valuable concepts in the rhetorical traingle like context, author, and audience for intent. Many of these points of the triangle have, thankfully, been reinstated and emphasized through the many different schools.

But, as I’ve said before, each new school of criticism only seems to acknowledge just one part of the triangle–except for Deconstruction which, at its worst, throws up its arms in an act of literary nihilism and says that meaning is “undecidable.” What would it look like if it acknowledged all parts of the rhetorical triangle, not just one? What if we married the princples of literary analysis and rhetorical analysis?

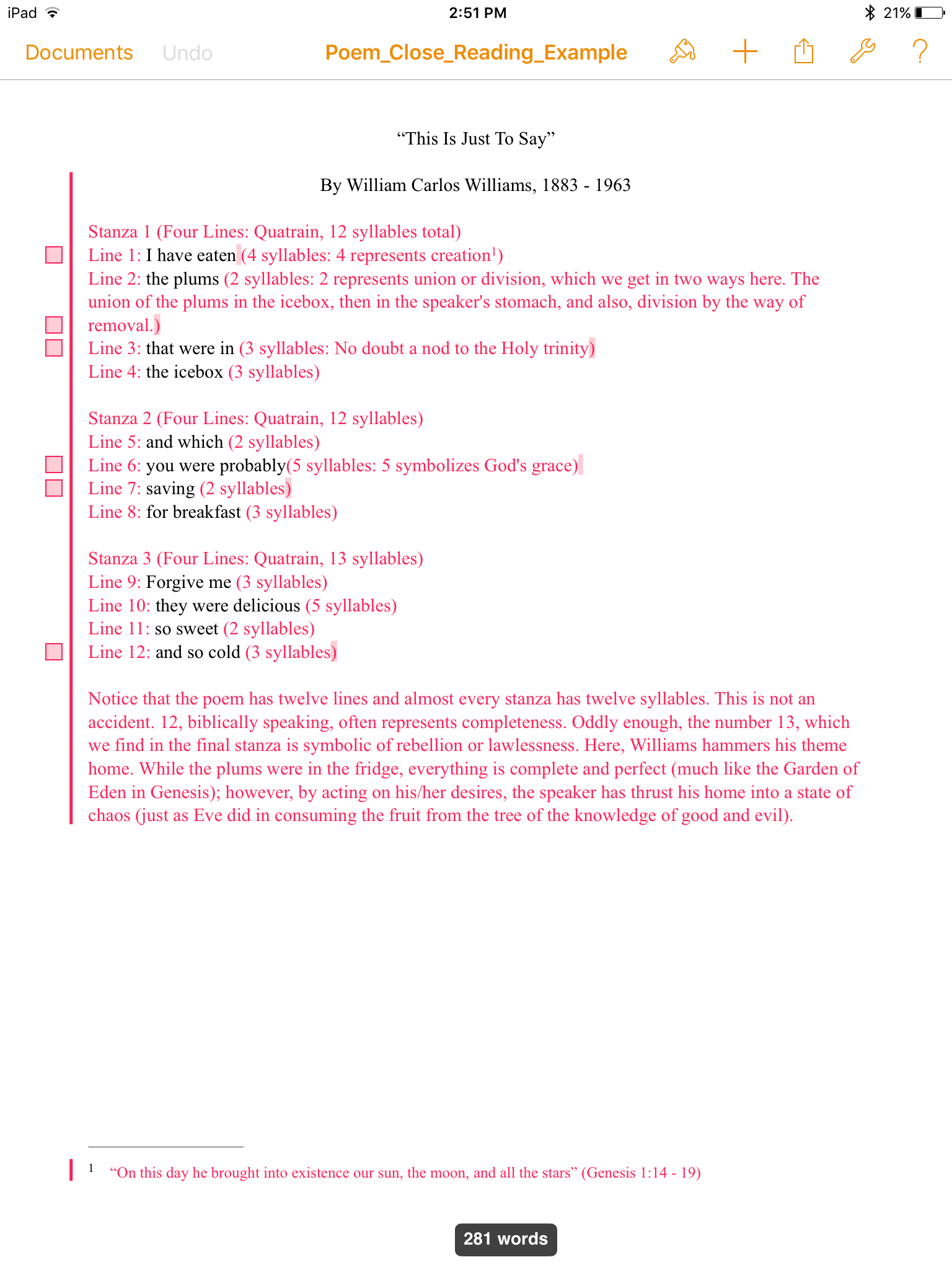

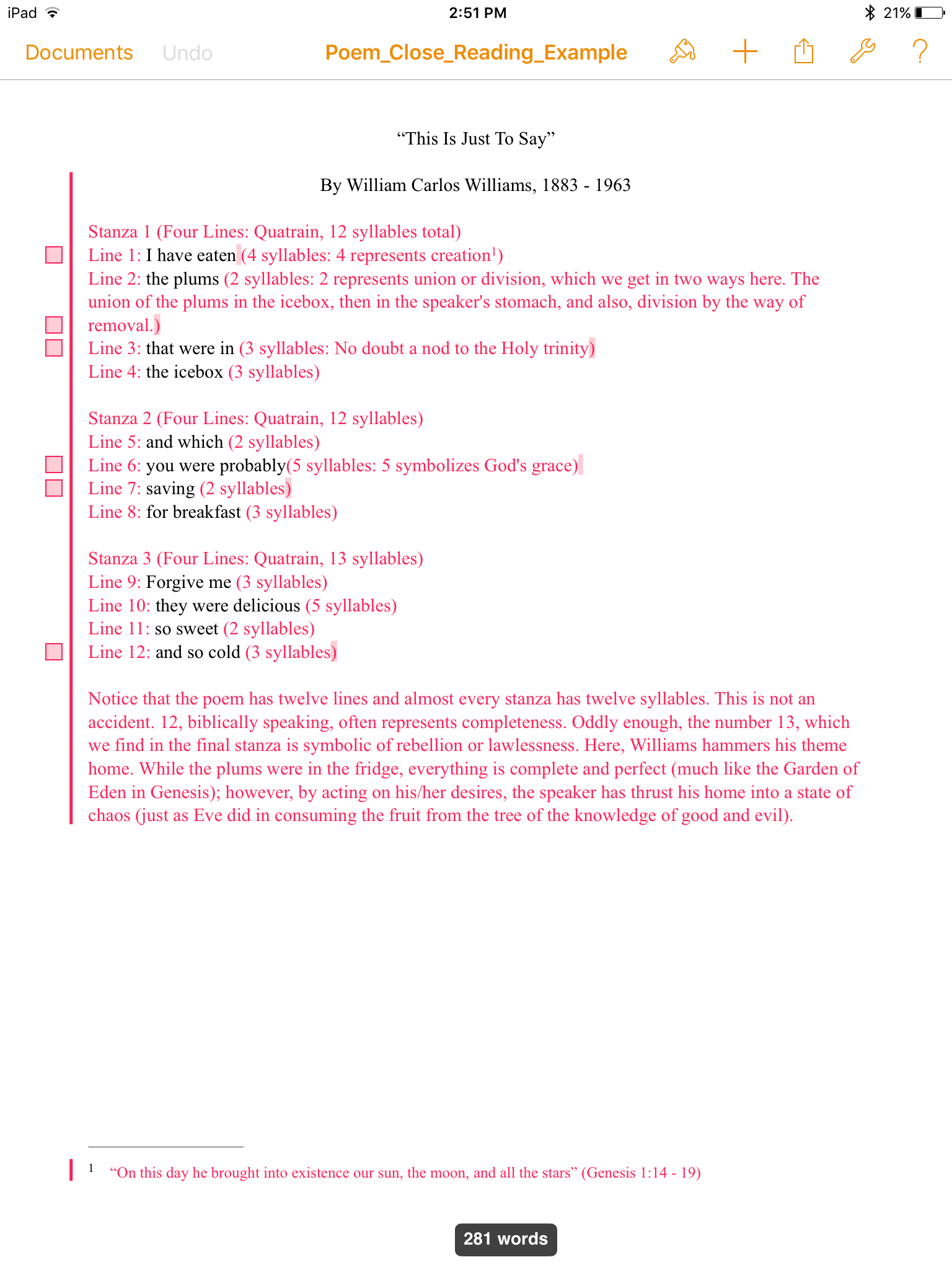

Let’s say we have a text, maybe “This is Just to Say” by William Carlos Williams. The first step should be to do an actual close reading, like this:

Post-It Note 1 (Line 1): This first line tells us a lot. First, we know that this is past tense, since it is “have eaten.” Second, this line is enjambed (it ends without punctuation in the middle of a sentence.). This suggests hesitation on the part of the speaker—the “I” of the poem. There is a clear sense of conflict in the speaker.

Post-It Note 2 (Line 2): Again, we have another enjambed line, putting special emphasis on the fruit itself. This choice seems very deliberate. The eating of forbidden fruit is a popular theme throughout Western literature (think Adam and Eve), and the speaker may be drawing that parallel.

Post-It Note 3 (Line 3): Line three, pauses again to emphasize the fruit’s non-existence and makes us consider its prior location as well.

Post-It Note 4 (Line 6): Here, the speaker introduces the second person, the “God” of the poem, who will, hopefully, forgive him/her.

Post-It Note 5 (Line 7): Notice that the line dwells on “saving,” which follows the line that introduces the “God” of the poem. Our speaker wants to be saved.

Post-It Note 6 (Line 12): This line which ends the poem may be a reference to the medieval view of hell. It was not a place of fire and brimstone, but a cold, cold home for sinners. The thinking was that the further away from God a person was, the further he/she was from God’s light.

This close reading observes the text itself and aims to decipher its “obvious” meaning. And since this is already a pretty simple poem, we know the theme is temptation. It is the tension between yielding and aversion. The privileged term here, seen through the speaker’s indulgence, is yielding, giving in. This, the poem tells us, is the better action. Of course, it is not that simple, since as we learn at the end that the act is both “sweet” and “cold,” signifying that has brought the speaker pleasure because it is delicous and pain because it has caused him or her guilt. The text is, therefore, in conflict with itself.

But in my close reading, I have also made historical and literary connections, which are not self-evident, not explicit. So the question is why? Clearly, I have a bias. I have imbued the text with what I see in it. I am actively constructing it in reader response. So we can say I have been influenced by my cultural landscape, particularly the hegemony of Christianity, as I draw connections between what I observe and with what I associate with what I observe.

And Williams has a bias too. His consciousness has also been shaped by the same cultural hegemony, corrupted by the institutional power of the Church, for the confessional nature of the poem highlights his own anixety over partaking in such a “sin.” Foucault, in his History of Sexuality, claims, “[O}ne does not confess without the presence or virtual presence of a partner who is not simply the interlocutor but the authority who requires confession.” The poem’s speaker’s pleasure may be blissful in the moment, but afterward, it leaves him or her empty and guilt-ridden, for which the only solution is confession. Such an attuitude concerning pleasure is contrary to the speaker’s (and by extention, Williams’s) own biological impulses, trapped in a Pavlovian cycle of pleasure always followed by pain.

Lastly, we must examine the context, the time and place in which the text was composed. Published in 1934, the poem is a product of its era, when, for the decade prior, there was the unbridled hedonism of Prohibition lurking beneath the surface of “dry” America, as all kinds of sexuality was celebrated by those who engaged in the counter-culture, but with the repeal of the 18th Amendment, returned puritanical denial and self-flagellation.

This approach, even as rushed, sloppy, and simplified as it is here, is what we need more of, an observation of all the points of the triangle, one that presents a more complete, complex, and thorough portrait of meaning, which hopefully gets even more complicated when we factor in things like race, gender, class, et cetera. Some may claim this is tedious–and I think it is–but it is also necessary. Criticism is designed to be just that.

Furthermore–and this should go without saying–this approach does not stake a claim on ultimate meaning. It is grounded in Cartesian uncertainity: It recognizes the subjectivity of experience. If anything, it is a Kierkegaardian leap of faith. But the important idea is that it demonstrates how the critic got to where they are. This idea is still very much in its infancy: There is more to be developed here, more to be scrutinized, more to be theorized, more to be tested, more to be investigated, more to be written and revised. But at least, it’s a start.

April 29, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

Lately, there’s been a lot of talk about the experiences of people of color in MFA programs. First, there was Junot Diaz’s piece at the New Yorker last year. And just recently, David Mura wrote up an essay on Gulf Coast‘s blog. Both of them describe their experiences as people of color in the MFA hegemony, and I have no doubt that their frustration is real. There are a lot of white people in MFA programs, and it can be alienating I’m sure. (We only had one person of color in my MFA cohort and only a handful of professors of color, and I cannot say how they did or did not feel. I did notice that race was rarely discussed but only because it seemed that the white people tended to write about white people and the people of color tended to write about people of color. I did not feel, fortunately, if it was brought up, that it would not be ignored or trivialized.) But in both articles, there seemed to be an underlining idea, one that made me somewhat uncomfortable as an artist. They suggested that writers have a certain responsiblity to depict their reality, which I agree with, but that comes with a caveat: that a writer’s reailty should consider the reality of others.

And this got me thinking.

#

In Mura’s article, “Student of Color in the Typical MFA Program,” he says that a lot of white people are ignorant to this topic of race, unwilling to discuss the ways they consciously and unconsciously uphold white supremacy in their fiction. He writes:

If and when the student of color voices her objections to the piece, more often than not, neither the white professor nor the other white students will respond to the actual critique; nor will they inquire further into why the student of color is making that critique.

They disregard this opportunity to discover their own whiteness, to investigate why a particular character is a stereotype, and potentially, right the problem. I think these are all fine ideas worth exploring. (I am, after all, Italian-American and, therefore, bleed marinara.) But there’s an implicit assumption, if the writing workshop recognizes and discusses and agrees upon this attempt to fix things in their stories, that I find problematic: Artists, with a little help from others, can fully control their message and its effects on the individual reader.

#

A few years ago, I was reading an article in College English by Gay Wilentz. It claimed that The Sun Also Rises was an anti-Semitic work, conveying the nation’s anxiety over the Jewish usurper. The author gave many examples and laid out her case as best she could, but it was something I didn’t buy. The novel seemed so much more complex than that. Sure, there were a lot of characters who hated Robert Cohn because he was Jewish, but I wasn’t sure if the novel necessarily endorsed that type of behavior. After all, Jake Barnes’s opening narration presents Cohn as a somewhat tragic figure. Barnes describes him as “very shy and a thoroughly nice boy,” who “never fought except in the gym.” He even tells us that the reason Cohn took up boxing in the first place is “to counteract the feeling of inferiority and shyness he felt on being treated like a Jew at Princeton.” If the novel is trying paint Cohn as a Jewish stereotype, it doesn’t seem to be very successful. Even later, when Barnes goes fishing with Bill, Bill asks him to say something pitiful. Barnes answers, “Robert Cohn.” That seems to run contrary to this idea of Cohn as the Jewish boogeyman. And furthermore, while the rest of the cast are quick to call Cohn a “kike,” Barnes, as far as I can remember, never utters the word himself. But instead of recognizing these points of contention, the critic ignored them: They weren’t relevant to her data set.

She had an argument, and she was going to prove it.

Most people would ask what was Hemingway’s point? They might even wish to summon the author through séance and ask him his reasoning, but I feel this too wouldn’t be very valuable. Why should we worship Hemingway’s analysis? He’s not God of the text, just the vehicle from which it came out. There’s a complexity there, and it’s not easy to say exactly what it is or is not.

And it’s not just in literature that I see this either. Tyler Shields, a photographer did a photo shoot with Glee cast member Heather Morris.

A few people said that these photos glamorize domestic violence, and the photographer himself later issued an apology. Now let’s actually look at some interpretations of these photographs.

In the first photo, the woman, who has a black eye, is restrained by the iron. She clamps down on the cord to bite it. She is dressed like a 50s housewife. The first way we can perceive the image is that it is a sexualized fantasy, depicting what some wife beaters probably masturbate to. But personally, that’s a little simplistic. She’s restrained because she’s bonded to domesticity, a burden the iron represents. Her husband, most likely, gave her that black eye. But the fact that she’s biting through the cord suggests resistance, the desire for escape. And if we look at the next photo, where she places the iron over the man’s crotch and smiles, there seems to be another message, and that’s one of empowerment. I’m not saying these are the only interpretations. And none are superior. But there does seem to be a problem with saying that because one of these interpretations angers us, that is no longer valuable or useful. It’s art, and it isn’t designed to have a specific, concrete meaning. That’s the beauty of it, the–as the deconstructionists would put–undecidability of it.

So why does the artist need to apologize? Should Shields have foreseen this possible consequence? And if he did, how could he correct it? There’s no doubt a meaning Shields perceives as viewer himself (not that his is the “correct” one). But let’s say someone mentioned this possible interpretation, and he reshoots. Won’t there be another argument against him–somewhere? Isn’t there something which will always rub someone the wrong way?

#

Roland Barthes, in his book Image, Text, Music, wrote: “To give an Author to a text is to impose upon that text a stop clause, to furnish it with a final signification, to close the writing.”

It seems like giving a text a critic does the same thing.

We assume that because the author has summoned the work into existence that he or she is God, but if we fool ourselves into believing this, then there is no further cause for investigation. But if we say that because an interpretation is valid and that interpretation evidences a message we disagree with, then the work must be condemned and extinguished, unworthy of appreciation or discussion.

But I think this too starts with the wrong supposition.

Art is an act of creation, not just on the behalf of the creator, but the individual viewer too. It is an act of two halves of the same soul coming together to create meaning, and that meaning exists uniquely between each reader and each author. If we impose our flawed and cherry-picked readings on all others–and the author–we do all art a disservice.

#

I was so excited my junior year of college. I had known I wanted to be a writer from the moment I failed physics my freshman year, and I was finally getting a chance to take a class in creative writing.

My excitement quickly subsided as I realized that I was the only person who actually wanted a career as an author. Everyone else, it seemed, took the class as an easy elective. Nonetheless, I persisted regardless, scribbling voluminous notes on people’s manuscripts that they tossed in the trash after class.

We spent the first half of the semester writing poetry, and in that time, I wrote two bland poems. One was an image poem; the other was about consumerism–or something like that. They were not very good poems, but I had little interest in writing poetry. I wanted to be a novelist.

I read anything I could get my hands on. I explored the Canon, read as many books off as many great novels lists as I could find, burned through the recent National Book Award and Pulitzer winners (including Diaz’s Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, which I loved). I spent afternoons in the library, and in the evenings, after work, I paged through Wikipedia trying to pick up every bit of literary history there was. I also was particularly fond of Bret Easton Ellis.

One of our first fiction workshops showcased one of my peers and me. I couldn’t wait to learn what the weaknesses were in my writing, places where the pacing sagged, where characters motivations were unclear, where the style could be sharper. I longed to learn the craft, the necessary elements in telling a story. All I had to go on, at that point, was what I picked up from the great fiction I had read and a few articles I had read online. I couldn’t wait to have it all explained by an expert.

I should have known what I was in for after we discussed the first author’s work.

My professor, an academic and poet (I use that term loosely as she has fewer artistic publications than I do and is at least twice my age. One of her poems that I found online told the story of how Oprah was at the foot of her bed and told her to go for a run or something. It was not a worthwhile read.), didn’t focus on the writer’s craft. Instead, she handed out a photocopy of the definition of heterosexism. She said that the writer’s liberal use of the word “faggot” conveyed a heterosexist attitude.

I found myself as the only voice of descent as the rest of the class sat in silence.

It wasn’t long before we moved on to my story, a near twenty page ode to Ellis. There was sex, men who couldn’t orgasm and woman who could, murder for hire, a double-cross, and sex. I do not think the story was well-crafted now, but I was young and immature and still learning as an artist. I had some idea that I was showing how some men may feel in society and how they go to crazy means in order to reassert their masculinity. It was a model of bad behavior that spoke for itself. Instead, my story was accompanied with the definition of misogyny. My professor said my story was inappropriate for class and expressed a hatred for women.

Needless to say, I wasn’t all that happy about it. At first, all I could muster when she asked for my opinion was that I felt like a douche.

However, after I thought about it, I tried to say it was pretty clear that my character was a scumbag, that people shouldn’t be going to the lengths he did, that I didn’t need to spell out what a bad man he was. I even referenced a letter from Chekov, who wrote:

You abuse me for objectivity, calling it indifference to good and evil, lack of ideals and ideas, and so on. You would have me, when I describe horse-stealers, say: “Stealing horses is an evil.” But that has been known for ages without my saying so. Let the jury judge them, it’s my job simply to show what sort of people they are.

But the conversation didn’t make any difference.

When I got my draft back, I learned that she had graded it as well. I “earned” a D-. (Who the fuck grades drafts, anyway?) That, I felt, was pretty unfair. I had written the longest story in the class, one that had a beginning, a middle, and end, one that had dialogue and description (a lot of description). And as far as I could tell, I was the only one who actually took the class seriously!

Her notes didn’t say anything about craft either. She didn’t tell me that acts needed to be shortened, that the plot was non-sensical, that the characters were unrealistic, that the symbolism didn’t work, or the theme wasn’t clear. She focused on the meaning, her meaning.

Of course, I’m not one to take defeat lightly. The first thing I did was appeal the grade to the dean, writing a two page letter on the multitudinous meanings of literature, citing everything I had learned from my theory classes. I gave a list of novels which, at some point in time, were deemed controversial and had graphic, shocking sexual and violent content.

My appeal was dismissed out of hand.

But again, I wasn’t going to roll over, and I did the one thing I could do: I wrote. I wrote a new story for my next workshop, one squarely aimed at my professor’s philosophy, one which would be so carefully written as to prevent any misinterpretation. I was going to be so damn clear and so damn moral that even Jeremy Collier would blush. I told the story of a writer who was attacked quite regularly for his perceived misogyny, who felt he was being misread because he thought of himself as a feminist. (I’ve always been known for my subtlety.) The story contained a plethora of footnotes that gave an overload of information. All profanity was excised, replaced with “[expletive deleted].” The protagonist is a bit of a jerk, but his favorite author is a female feminist poet (the poet part was an attempt to suck up to my professor so I wouldn’t fail), who he talks to early on about something unrelated to the plot. And the climax takes place at a reading, where a radical female feminist stands up to shoot him, but of course, even that violence I neutered. Her gun shot not bullets but a flag that read, “Bang!”

It was not a very good story, but I thought the message was clear: Feminism is good, but radicalism isn’t.

The day of the workshop came, and nobody seemed to have much to say, not even my professor. At the end of class, she handed me back my manuscript, and I searched through and read her notes. She highlighted the climax, where I had added a footnote explaining who my antagonist was and why she was a bad person and how she promoted the wrong brand of feminism, essentially that being a radical separatist was bad.

My professor asked, however, “Why do you want to depict feminists this way?”

#

David Mura and Junot Diaz both teach at a writer’s conference exclusively for writers of color, called The Voices of Our Naton Association. Mura writes:

On a larger level, the student of color in a VONA class doesn’t have to spend time arguing with her classmates about whether racism exists or whether institutions and individuals in our society subscribe to and practice various forms of racial supremacy. Nor does the student have to spend time arguing about the validity of a connection between creative writing and social justice.

And there’s a part of me that agrees with that last bit about creative writing and social justice. I think that artists don’t write exclusively to tell a story: They have a message–and they should. But it doesn’t mean that it’s the only reason they write. It’s a pretty complicated affair, and fiction doesn’t serve just one person. Joyce didn’t like what he saw people doing in Ireland, but that’s not the only reason he wrote what he wrote. He wanted to convey, according to me, consciousness, the subjectivity of experience and perception, the cost of becoming an artist, the paralysis that infected Irish individuals, the beauty of sex, the Irish identity, his disgust with the Church. But he also wanted to write beautifully and tell a story and make people feel things. And he never does so didactically.

I don’t think we can have our cake here and eat it too though. There’s a difference between writing an essay and writing a story. An essay’s meaning is not up for debate, for the most part: It is a reasoned, logical argument. It’s meaning is fixed and can be defended or attacked. Frankly, it’s a better medium for making a point. A story, however, never once commits itself to one idea only. It is not a clear cut argument: It is a collection of evidence that can be interpreted and enjoyed or interpreted and hated.

And we are utterly helpless to control it. It’s that last part that really frustrates everyone else, but I’m OK with that.

I’m not in the business of pleasing others. I don’t write because I want to confirm your biases. I don’t write to make you feel better about yourself. I’m not trying to, as Vonnegut said, open my window and make love to the world because I know I’ll catch cold. Instead, I write to show you the reality I perceive, the world I inhabit.

We are the masters of our own little universes: Critics be damned.