June 19, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

Let’s be honest: I’m one bitter bastard. I got into this game because I wanted to write great fiction, because I wanted to reinvent the literary discourse while, at the same time, nodding my head to those great masters who cemented the tradition and inspired me in the first place; however, the further I get along (and the more I read), the more often I find myself frustrated and alone. When I was in grad school, I didn’t find too many people who shared that dream. There were some, of course, but most seemed content to write because they liked it, which is a fine reason to do it. A few were interested in money and were the most indignant when it came to used books. (These people I found to be the most insufferable. If you’re upset that consumers want to buy your book for less, it does not mean they are bad people or they are purposely fucking you. You indebted yourself to a monopolistic corporation in order to reach a larger audience: Get over it or negotate a bigger advance.) But probably most upsetting were those who had no connection to the tradition, no real knowledge of literature, and no real talent. These students tended to be the ones who left with books deals and agents. And this is something, I think, is endemic to the MFA hedgemony. Writers are pushed into the wild without real training or skill, and they, in turn, help to shape the literary discourse in their own image, which marginalizes quality fiction.

#

I read an excerpt from a novel that was getting a lot of press and praise at the time. It was in Narrative, and I haven’t really heard much about the novel or the author since then. But I read it without expectation. It told the story a young woman who goes to a party, discovers it’s kind of a lesbian orgy, goes home, and then realizes she’s in love with a woman from the party.

Most of the dialogue is banal and useless: “Patsy must have spotted you, the pale woman said now. Iris smiled. I’m Sylvia, the woman said. Iris, Iris said.”

When you’re writing, you have the ability to go anywhere and show anything. So why the hell did this author choose to waste ten seconds of my time? How about a sense of conflict? But in this excerpt, that problem is buried.

Iris put her hand to her hair to fix it, and the dwarf with the white fez came by. Champagne? he said. Oh, please, Iris said. Rose looked at her. Well, here I am thinking, Look at this little bumpkin, and here you are, having your way with Armand and who knows what else. Shame on me, she said. Oyster? Iris opened her mouth.

This was not the kind of party where you said, Oh, I’ve never eaten oysters, or, Oh, gosh, they look wet and disgusting, which they really did. If oysters were the path to parties like these and beautiful, dazzling, dark Rose Sawyer, Iris thought she could toss back oysters like cold beer on a summer day. She managed two and chased them with champagne.

Iris clearly has never had an experience like this, and that’s where the problem lays. But she doesn’t seem to be doing little more than observing. Instead, the author emphasizes description over character and reaction:

“Who should lead?” Rose said.

“I could,” Iris said quietly.

“But you don’t want to,” Rose said, and she put a strong arm around Iris’s waist. All Iris’s dancing, her show routines, waltzing with her father, the senior-year parties with Harry Bledsoe and Jim Cummings, who were the best dancers in Windsor, faded away. She was dancing for the first time, right now, her face against Rose’s smooth, powdered cheek. Breast to red silk breast, thigh to black silk thigh. They did two promenades and a slow twist, as if they’d been practicing, and Rose pulled Iris back to the divan. More champagne appeared.

Again, we get very little in the way of conflict or anything interesting. The character, in this excerpt, is so unwilling to do anything more than observe and hold momentary, somewhat thematically relevant conversations. Why isn’t she doing something? Just because she’s scared or beguiled or lost doesn’t mean Iris should be useless. She has choices to make, more interesting choices with actual stakes attached, not a dishonest twist to generate interest after your reader has fallen asleep. But the writer doesn’t seem interested in telling a compelling story or even creating an character we care about or want to know about: The writer is, like most players in literary fiction, too concerned with crafting gorgeous prose and not what it expresses.

And though this may not be indictative of the work as a whole, you’d think an excerpt in an important magazine like Narrative would be one, complete and two, interesting. But instead, we’re given tedium and useless description, two things readers tend to skip.

This is why literary fiction can’t find broad appeal.

#

It’s pretty easy to identify the problem when it presents itself on the page, but it’s a little more difficult to look at that same problem and cite it institutionally. If literary fiction’s greatest threat manifests itself through boredom, the question arises: Why? The answer, I believe, is surprisingly simple. We have the blind leading the blind. Few writers running, publishing, or submitting to the big, little magazines these days have mastered the form. They rely on instinct and intuition. They write, edit, and decide with their gut. They don’t seem to have a set of objective criteria that determines good writing, and if they do, there is but one consideration: the prose. These editors and writers are the most disappointing of all. They spent their early years reciting Virginia Woolf and lines of poetry but never truly took the time to discern what made that prose better than others. These writers are quick to object to theory and rhetoric. They don’t like definitions or structures. They merely listen. Does it sound right? Often times, the work they produce or publish is little more than a fragment, an ancedote, inconsequential, not at all a story.

I too grew up loving the music of language (and I still find sentences or images that make me stop reading and write the words on my thigh with a finger), but I’m not foolish enough to say that is the sole criterion on which to judge. Good sentences are a given. They should not be considered special. A writer with sloppy prose is not worth reading regardless, and a writer with masterful prose and nothing to say is even worse.

Many of these writers eschew the tradition. They claim that form is limiting, that they need the freedom of a true artist. But if you have yet to learn the basics, what do you really have to deconstruct? How can you experiment with something you don’t fully understand? The budding bodybuilder does not start with drop sets and complexes: They learn the movement first. And can we really say that artists are hamstringed by their own ever-expanding knowledge? Does the musician suffer because he learns scales and modes? Is the painter stifled when she practices composition? I think not; in fact, that mastery most likely enhances their abilities. Yet, rarely, except with genre writers or writers for the screen, do I hear anyone talk about the governing laws of story. All great artists honed their craft. They emulated their forebearers. They practiced.

Hunter S. Thompson famously wrote out sentences from The Great Gatsby. Ben Franklin memorized articles from The Spectator. Joyce said he was content to go down in history as a scissors and paste man. But they didn’t just learn to write sentences. They discovered how a work was constructed. They processed the elements that comprised its composition. They taught themselves to search for le mot juste and the best available means of persuasion. They perfected the form before they destroyed it.

#

One of the most obnoxious trends in recent years is the rise of flash fiction. Editors have propped it up, thinking it “competes” with Facebook and video games and television. (It doesn’t. They’re entirely different media.) Because of its brevity, flash fiction, usually under 1000 words, can be finished before you put away your dick after a piss, but, in most cases, I would not describe it as a satisfying experience. At its best, it is a first paragraph or ten from an otherwise incomplete story.

Here’s an example from Tin House’s Flash Fridays.

The story, titled “The Girls Where You Live,” relates the uninteresting tale of a young man (our narrator) who meets up with a homeless guy who tells the narrator to “not eat the pussy.” The narrator trades the homeless man two cigarettes for seventy-five cents. The author then follows:

I was drunk. We were all drunk it seemed. Everyone I knew. We drank until we felt like copies of ourselves, which would vanish, and whatever plans we’d made too, in the morning’s first blue light. I saw the man, and the cashier and the store, which was plastered, ceiling to linoleum, with liquor, beer, cigarette, and cigarillo adverts in bleary swathes of imagery, as through a fogged window polished with your hand. And in the corner near the door, there was a coin-operated candy machine half-full with jellybeans, except where were the children? Where were the mothers who’d dug through their purses and found one last quarter?

“That’s not very gentlemanly,” I managed.

In a story of less than 1000 words, this author, who is somehow or another an MFA candidate at Johns Hopkins, wastes the reader’s time with an expositional onslaught of pseudo-philosophy. And our conflict? He mildly disagrees with the homeless man.

This is followed by some questions about where the narrator is from, and the narrator answers that there were many pretty girls in his hometown. They converse about the girls’s hygiene, and the story ends with:

“I’ve met kids like you, you know. “ He said, “I’ll bet your mamma traded you silver dollars for your baby teeth, didn’t she? I bet she smelled all over just like the palm of her hand. When I lost a tooth, when I put it beneath my pillow, do you know what I found in the morning? I found a tooth. And there was still a bit of blood on it. And it was mine. And I buried it in the yard like a dog.” He laughed madly again, which shook the whole of him and rattled his eyes.

I left him there, laughing and gasping, and hocking loogies into the stormdrain.

What? I’ve offered a large portion of the story here, but even if I wasn’t so curt in my description, I doubt you’d have any better understanding of this than I do. Just what the fuck did I read? I get that the author believes he’s highlighted something profound, something about class, but I just don’t see it. This might be amusing if you still get a chuckle from hearing about pussy. (I’ve had sex, and I’m over the giggles. Thanks.) Otherwise, what’s the point? There’s very little sense of conflict here. The description is a vehicle only for itself. The dialogue doesn’t advance the narrative (if anything, it delays it). And the characters seem poorly drawn and one dimensional. Where’s the arc? Where’s the plot? Where is any evidence of craftsmanship?

Of course, this is no mere aberration. Here’s one from McSweeney’s Quarterly, called “Don’t Get Distracted.”

It begins, “One morning in January, I was walking to my studio feeling happy because I had spent the night with a new lover. I passed a mother and father carrying a baby…. A man walking in front of me turned around and said that it must be the couple’s first baby, because otherwise they would have covered its head….”

The first sentence is mostly forgettable. Why does this story start with “Everything is great.” Characters whose lives are perfect are boring. Then some insignificant man says something significant. (This seems to be a popular trope in shit fiction.)

Our narrator and the man walk together and converse, and he tells her, “Ladies must always walk on the inside.”

Our narrator asks why, and the man responds, “Ladies must walk on the inside because if they walk on the outside, it means that they’re for sale. If a man says he loves you, pay attention to which side of the sidewalk he lets you walk on.”

She thanks him for walking her home and the conversation, and he tells her, “Remember, don’t get distracted.”

And the story ends with her reply, “I’ll try not to.”

Seriously? Seriously? Fuck you.

Again, there isn’t much more to that story than what I offer here. How is this publishable? How is this quality work? Who does this appeal to? It’s banal. It’s trivial. It’s not interesting. The theme here, about what men do for their women, isn’t explored at all. Does the narrator fall in love with the man she’s walking with? Does she reconsider her relationship with her new lover? Does she realize that she loves her lover? I don’t fucking know. You know why?–because it’s fucking hidden. What is this, a goddamn scavenger hunt? There’s not enough detail to make analysis worthwhile. The author doesn’t seem aware of plot or structure. The author doesn’t use the best available means of persuasion. The author doesn’t even seem to recognize that a theme without context or clarity is no theme at all. And while we have a symbol in the form of the sidewalk, it doesn’t help if that symbol doesn’t illuminate anything nor is its meaning explained.

And just one more example of the “short-short story,” which is apocryphally attributed to Hemingway: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.”

First, if Hemingway did write this, it’s by far one of his worst, and lacks the brilliance of his stories like “Hills Like White Elephants” or “The Short, Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” Second, this isn’t a story. It might be the beginning of a story, but it’s certainly not a complete one. What is the status quo? Fuck if I know. What is the inciting incident? Baby dies? What is the debate and break into act two? Who knows? The midpoint? Suck a dick. The third act twist? Fuck off. The climax and resolution? Somebody is poor.

Wow, I am blown away.

Who are my protagonist and antagonist?

What is the point of view?

What is the conflict?

What is the setting?

Are there symbols?

What is the theme?

I know I may seem like the crotchety old man here, but flash fiction is not a great innovation in storytelling. It’s not subverting the form for any clear purpose. It doesn’t change the short fiction form because of its limitations. And it is certainly not learning vaulable lessons from the micro content we find on the web. I’m not saying that YouTube and Twitter can’t be inspirations or help to mold the form–they can–but if all we’re getting out of those models is that people like things short, we’re not asking the right questions.

#

If there is one writer who offered more formal innovation than any other to English writing, it must be James Joyce. In one book, he invented and reinvented English prose and style. Ulysses is a towering momument of the possibilities of literature, the same way Watchmen is to comics or The Odyssey is to epics. But the novel took Joyce seven years to write. He mined every form of media to make an enormous compendium of forms, which still adhered to the conventions of story and the novel. (If you deconstruct it, you will still find all the necessary elements of story.) Of course, he was forty years old when he wrote it.

But let’s go back a few years, before he was a God of English prose, when he was still finding his way as an artist. Whenever people talk about Dubliners, they usually bring up one of two stories: “Araby” and “The Dead,” two master works in the collection. Rarely, do people talk about “Counterparts” or “Clay” or “Two Gallants.” Some of the stories in Dubliners are better than others, and if you compare something brilliant, like “Araby,” with something not very good, like “After the Race,” it’s pretty clear that even Joyce struggled with the form.

“After the Race” was one of the first stories Joyce wrote, published in 1904 in The Irish Homestead, and it’s easy to tell. The prose is great, as is to be expected, but there is very little in the way of a narrative or causality. The story doesn’t seem to be much more than an insignificant collection of scenes strung together. (Yes, there is a theme about class and money, but it feels lost in the shuffle.) Worst of all, it fails to showcase Joyce’s finest skills as a writer: human interaction. Whether alone or with others, Joyce’s characters, from Molly Bloom to Gabriel Conroy, spend the majority of their stories talking about important things, and I don’t just mean things like economics and Shakespeare. They are in constant conflict. Every word is a bullet in the larger Alderian power struggle. In Jimmy Doyle, the protagonist of “After the Race,” is little more than a detached observer. But even his consciousness isn’t all that interesting. And what few choices he does make are given to us in summary rather than action:

They drank to Ireland, England, France, Hungary, the United States of America. Jimmy made a speech, a long speech, Villona saying: —Hear! Hear! whenever there was a pause. There was a great clapping of hands when sat down. It must have been a good speech. Farley clapped him on the back and laughed loudly. What jovial fellows! What good company they were!

Now I get that Joyce is trying to show Jimmy’s ignorance, how he can’t see that his own friends think he’s an utter jackass, but Joyce’s over-reliance on summary deadens that effect. Had he had the characters interact in a real, complete scene, the story would be much more significant.

But again, Joyce was a young man then. He wasn’t experimenting: He was learning. And even still, he had already grasped theme and irony better than most veteran writers, but he wasn’t a master of the form. He knew he had more practice ahead of him.

I don’t see many young writers with this kind of awareness, who consciously work on their weaknesses. If you read Dubliners to completion, you can see, in a non-linear fashion, the growth of one of the twentieth century’s greatest artists, from ignorance of form to mastery of it.

#

In our quest for the new and exciting, we have embraced the mediocre and inconsequential. I doubt very much that Hemingway or Fitzgerald, Dostoyevsky or Tolstoy would ever make their prose their only concern. The masters demonstrated through their work that they gave care to plot, character, theme, symbol, conlict, setting–all the the conventions of story. And when they did subvert our expectations, there was a discernable reason, because the old ways weren’t enough to express it.

I too want to subvert the tradition, but I also respect it. There are many fine things we have gained from it, but few people these days are interested in textbook fiction, the kind we study in college classrooms. They seem to think that the ability to analyze a work lessens it, that discerning the truth of it robs it of its glory.

It’s funny. I always thought of myself as a literary revolutionary, someone who would overthrow the order. Yet most of the work I find does it in ways I don’t particularly agree with, from people unaware of what came before them, which seems to make me the old-fashioned traditionalist, but when I think about it, if bad, incomplete stories are what’s trendy, I guess maybe I am part of the revolution–just on the losing side

June 14, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

When I was young and stupid and frivolous, I thought following a form was the most limiting thing you could do as a writer. I liked pushing boundaries, discovering new horizons, creating something truly new and unique. And even though I had a way with words, I had difficulty turning in a well-composed essay. Don’t get me wrong now. My papers were never awful, but invariably, I would get it back with comments critiquing the organization and the buried argument. Of course, it wasn’t until I started teaching that I really learned how to fix those problems. I did, of course, get better over time, but teaching really put things in perspective for me and I was able to find a common thread between the academic essay and storytelling.

The academic essay is probably one of the easiest forms to understand but one of the hardest to master. It’s simplicity is its greatest strength, and the part that trips up most budding writers. It’s essentially three parts: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. The introduction presents the topic and what others have said about the subject, which leads logically to your thesis, the heart of your paper, the main argument which you intend to prove. The body offers evidence and interpretation of that evidence which supports the paper’s thesis. The conclusion provides an interpretation of the argument you’ve presented and explains its significance to your field/subject/audience. And the short story or novel or poem can follow those same rules.

A story’s theme is its thesis, the answer to question that drives the writer to keep writing to the end, to discover what possibilities exist. A great story aims to prove something the same way an academic essay does. And typically, if the writer is any good, he or she plants those seeds in the very first paragraph–if not lines.

Let’s look at Joyce’s “Araby” as an example. The story itself is a simple one: Boy meets girl, falls in love, learns she wants to go to the festival but can’t, decides to buy her a present, but ends up leaving empty handed. This is not what I would call exciting. I’ve done that on a weekend (and for most of my adolesent life). So what? But that’s the thing: It’s not just the events that are important, but how they are told and experienced by the narrator which determines the genius of the story. The work dwells heavily on the theme of love vs. lust and learning the difference in the soul-crushing wasteland of Irish-Catholic Dublin.

The story begins:

North Richmond Street, being blind, was a quiet street except at the hour when the Christian Brothers’ School set the boys free. An uninhabited house of two storeys stood at the blind end, detached from its neighbours in a square ground. The other houses of the street, conscious of decent lives within them, gazed at one another with brown imperturbable faces.

The first paragraph alone sets up the narrator’s problem. His street in Dublin is “blind.” And even though he’s saying that it’s a dead end, that diction choice parallels the final image of the story as the boy stumbles in the darkness and his eyes burn with anguish. Joyce is implictly showing us the problem of the story, using his theme and symbol to do so. The street is a stand in for our narrator. He too finds a dead end in his “love” for Madgen’s sister, but also, the choice of blind alludes to his own blindness, his inability to differentiate between love and lust. And notice the end of the first sentence, the reversal that occurs. The only time the street is happy is when the school “sets the boys free.” Again, this is no mistake on the part of the author. Joyce is saying that casting off the fetters of religion is the only way to achieve happiness and enlightenment. Lust is OK–as long as you’re OK with it too. It’s a human emotion that we all feel. Why should we surpress it? Why should we be embarassed by it? Why should we bow down to the mores of the Church?

Of course, the next paragraph elaborates on that idea further, with a description of the narrator’s house, and it is this theme the story keeps coming back to.

Later on, Joyce writes:

One evening I went into the back drawing-room in which the priest had died. It was a dark rainy evening and there was no sound in the house…. All my senses seemed to desire to veil themselves and, feeling that I was about to slip from them, I pressed the palms of my hands together until they trembled, murmuring:

–O love! O love! many times.

This is the thesis of the story, the theme, the part where the author most obviously addresses the question. Here we have the conflict of religion and instinct, of love and lust. The boy is praying, but the diction choices betray his innocence. It doesn’t sound like a typical prayer but, instead, more like masturbation or Onanism, which is forbidden. But the boy cries out in “love” because he doesn’t know what to do with those feelings. He doesn’t know what that twitching in his pants means, and he mistakes them for love. And his dialogue with Madgen’s sister only furthers that point:

She asked me was I going to Araby. I forgot whether I answered yes or no. It would be a splendid bazaar, she said; she would love to go.

–And why can’t you? I asked.

While she spoke she turned a silver bracelet round and round her wrist. She could not go, she said, because there would be a retreat that week in her convent. Her brother and two other boys were fighting for their caps and I was alone at the railings. She held one of the spikes, bowing her head towards me. The light from the lamp opposite our door caught the white curve of her neck, lit up her hair that rested there and, falling, lit up the hand upon the railing. It fell over one side of her dress and caught the white border of a petticoat, just visible as she stood at ease.

–It’s well for you, she said.

–If I go, I said, I will bring you something.

This exchange highlights her absolute lack of interest in the narrator, and his failure to recognize it. Here is a girl who’s just being nice, talking to this slightly younger, immature boy, and when he says he will go, she says, “It’s well for you.” That might be one of the most backhanded things she could have said. She really doesn’t care if he goes. She’s only humoring him with the conversation. But the narrator is too blinded by “love” to notice.

It’s only in the darkness of the bazaar, when the narrator witnesses the bawdy talk of a young English woman and some boys (not at all Arabian or exotic as he was led to believe) that he has his ephipany:

At the door of the stall a young lady was talking and laughing with two young gentlemen. I remarked their English accents and listened vaguely to their conversation.

–O, I never said such a thing!

–O, but you did!

–O, but I didn’t!

–Didn’t she say that?

–Yes. I heard her.

–O, there’s a… fib!

Observing me the young lady came over and asked me did I wish to buy anything. The tone of her voice was not encouraging; she seemed to have spoken to me out of a sense of duty. I looked humbly at the great jars that stood like eastern guards at either side of the dark entrance to the stall and murmured:

–No, thank you.

The young lady changed the position of one of the vases and went back to the two young men. They began to talk of the same subject. Once or twice the young lady glanced at me over her shoulder.

This is the moment when things become clear for him. We aren’t privvy to the entire conversation, but we can assume by her denial that it’s something “bad,” something which she feels the need to deny three times (and look over her shoulder at the boy). (It was improper to write about sex in the early 1900s, after all.) The narrator is coming to grips with his own blindness, learning that the emotion he feels is not love: He wants Madgen’s sister sexually, not romantically. He now sees himself “as a creature driven and derided by vanity; and [his] eyes burned with anguish and anger,” which completes the cycle.

We begin with an introduction of the subject (religion and instinct/love and lust), then we get our thesis (confusing one for the other), then our body (the boy’s story goal, his journey to the bazaar, and not buying a present), and finally our conclusion (recognizing the difference, the “so what?” moment of the story).

Every great story should aim to let its theme inform it the same way. It must the infect the work entirely. It may not lead to an ephiphany like Joyce’s work, but regardless of its techinque, it still follows the story form and addresses its story question. It must be there from the start and seen through to the end. Bad or unsuccessful stories make the mistake of ignoring theme or misusing it or undermining what they are trying to say, but great stories dwell on it, return it time and time again. Without it, all you have is a series of events that aren’t worth reading in the first place.

June 11, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

When it comes to plot, structure, and form, people too often confuse one for the other and discussing all three doesn’t exactly help. However, all three are an extension of the same source and must be viewed as blocks which build one on top of the other, originating from the story’s theme.

I like to think of it this way:

Theme determines form: form determines structure: structure determines plot.

With that said, we’ll start at the macro level and work our way down.

Plot

Plot, in its most basic description, is nothing more than a series of events which happen over the course of a story. E. M. Forster, in Aspects of the Novel, gives the following definition: “A plot is…a narrative of events, the emphasis falling on causality. ‘The king died and then the queen died’ is a story. ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief’ is a plot.” Unlike Forster, I don’t see much of a distinction between plot and story; however, his emphasis on causality is of great importance.

#

Rob DiCristino, of the Ugly Club Podcast, introduced me to a wonderful exercise for plot, which he learned from Matt Stone and Trey Parker of South Park. Apparently, the writers gave a lecture on narrative at some film school or another. (I am ignorant to most of the details.) And they said when they first started working on the show, they would write out the events of the story and link them together with the phrase “and then.” In other words, they plot it like so: “Cartman ate chicken wings, and then he went to the bathroom.” It wasn’t long before the writers recognized the flaw in this model. It didn’t emphasize causation–what good stories are all about. And they modified the template accordingly. Instead of writing “and then,” they wrote “therefore.” So “Cartman ate chicken wings, and then he went to the bathroom” became “Cartman ate chicken wings, and therefore he went to the bathroom.” Of course, what if the first event was undermined in some way? This too did they plan for. In those instances, they wrote “but.” So now we have “Cartman ate chicken wings and needed to go to the bathroom, but he was stopped by Mr. Garrison.”

This, I think, is one of the finest and simplest ways to look at a narrative.

Each event is not seperate or disparate, unrelated and cut off, but a larger part in a causal chain.

#

My writing mentor, Bob Mooney, was a student of the late, great John Gardner and his advice to me was often verbatim from one of Gardner’s books. While he oversaw my thesis, Bob would write out little aphorisms on the manuscript. When I had too much summary, he would write, like Henry James used to, “Dramatize! Dramatize!” But there was one that really stuck with me: “There are only two kinds of plots: Someone goes on a journey or a stranger comes to town.” This is one of those old apochraphals that Gardner supposedly said, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Bob had heard from the man himself. But when I thought about it, I realized, as much as I didn’t want to admit that such a binary could exist in art, it’s pretty damn true. Just think about all the great works in literature. The Odyssey: Someone goes on a journey. Beowulf: A stranger comes to town. Hamlet: Someone goes on a journey. The Tempest: A stranger comes to town.

And if you think about it, it’s really the expression of the same thing: It’s all a matter of perspective. The Dark Knight is a story of a stranger (The Joker) coming to town–a threat to the status quo–but if you flip it on it’s head and look at it not from Batman’s perspective but The Joker’s, it’s his journey.

Plot is a disruption of the ordinary and the effort to restore it but slightly improved. Of course, a good plot is not so simple. The master’s show us that these events don’t just exist to further the plot but to demonstrate something larger.

#

In Paul Greenaway’s The Cook, The Thief, The Wife, and Her Lover, the titular wife is trapped in a marriage to a loud-mouth gangster who spends his time in an opulent restaurant, pontificating about shit and sex, and she finds love in a bookish professor who eats alone (a stranger comes to town). Every action of the film relates to its themes of high vs. low pleasures–shitting, eating, and fucking vs. culture and love. Our heros consummate their relationship in the restaurant’s bathroom, then move to the kitchen, and finally his study. It is a literal movement towards those higher pleasures. Of course, the thief of the title tries to drag them back, using those lower pleasures: He mashes peas in the the professor’s book, insults his wife about her regularity, and force feeds the professor the pages of his own books. These events are not arbitrary. They are ripe for analysis. They communicate the grandness of this work of art. Plot, ultimately, is a reflection of theme.

Structure

Structure isn’t as complicated as most people make it out to be. It’s just like a good academic essay. There’s an introduction which explains the subject and sets out a point that it will prove, a body which proves the thesis, and a conclusion that wraps it up and answers that question of “So What?” It can vary here and there. It can be linear or non-linear. It can be logical or illogical. But at the end of the day, it’s all, more or less, the same thing: a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Of course, we can break that down a little further.

(The following breakdown is a bastardization of a variety of sources, most notably, Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat.)

Beginning/Act One

- Status Quo/Something’s Missing: This is world before the disruption. Things are mostly copacetic. It’s Luke living on the farm with his aunt and uncle in Star Wars. Of course, even though people are happy and there are no threats, there’s still something missing from our main character’s life. In Star Wars, Luke is looking for a life of adventure, but on the farm, he’s not getting it.

- Inciting Incident: This is the moment that changes everything. This is when the bad guy shows up or the telegram in the mail. To return to the Star Wars example, it is finding the message from Princess Leia.

- Debate/Theme Stated: Of course, change is scary, and no one will do so willingly. Luke wants to join Obi-Wan on his adventure, but he must attend to his duties on the farm…

- Can’t Go Home Again/Choose Act Two: This is when the choice becomes clear for the protagonist. He or she is no longer questioning themselves. Whatever was holding them back is gone. Luke returns home to find his aunt and uncle have been murdered, tying together his quest for adventure and revenge: He can leave with Obi-Wan and take on the Empire.

Middle/Act Two

- The First Obstacle/Shit Just Got Real: This is the first roadblock in our hero’s path. They have a clear goal now, but there’s a hurdle they have to clear first. Even though Luke knows he has to rescue the princess, he doesn’t know how he will get there; therefore, he must find himself a pilot, which he does in the form of Han Solo.

- B Story: This is the nugget of the story, the subplot that emphasizes the theme. It is a nice little distraction to the events. Typically, this comes in the form of a love story, but of course, there are other possibilities as well. Luke and company have to board the Death Star (and evade Jabba), but they won’t be get there for a while, so, in that time, Obi-Wan can give him a little sage advice and training: Use the force; trust your instincts.

- Midpoint: Depending on whether the story is a tragedy or success, this is the point where everything is great or terrible. It is, at this point, our hero’s greatest success or failure. The hero has finally reached his goal. Luke boards the Death Star and saves the princess. However, things quickly go downhill from here.

- Bad Guys Close In/You’re Surrounded: The hero is surrounded and his success is short lived. He has to find a way out, which he does–only to find himself in an even worse situation. Luke has saved Leia, but they end up in the trash disposal with some kind of killer trash snake. And the walls are closing in. They’re all going to die!

- All is Lost/Out of the Frying Pan into the Fire: The hero has escaped one certain and found himself in another. The mentor dies. The odds are stacked against them. They’ve been going the wrong way. Obi-Wan sacrifies himself for Luke, and our heroes must battle their way out of the Death Star.

End/Act Three

- Third Act Twist: This is the ultimate change in direction. Our hero is done licking his wounds and being a bitch. He realizes what he must do to save the day. He puts on his big boy boots and flies straight towards the enemy. The Rebels decide to launch an assault on the Death Star, and they know just where to shoot.

- The Showdown: The villain and hero come face-to-face in a climatic battle. Things here will either go one way or the other: The hero wins or the villain does. Luke leads the Rebels to the Death Star, trusts his instincts (which calls back to our B Story), and takes it down with his torpedoes with Han’s help.

- Resolution: Everything returns back to normal. Our hero has accomplished his story goal and his character goal. He has changed for the better. This is the result of his happy (or unhappy) ending. Luke and company are given their commendations and everyone smiles for the camera.

Form

This is the most interesting and overlooked piece of the puzzle. Of course, it’s also the most difficult. But done right, this is a sign of absolute genius. It is an atom bomb that change an either genre in one drop. Form is the greatest expression of theme an author has. It is a question of how best to reflect the considerations at the heart of a work and often leads to innovation. It is a reconsideration of what that modality has to offer.

Works like As I Lay Dying, The Sound and The Fury, Naked Lunch, Watchmen, Pulp Fiction, Annie Hall, and Ulysses demonstrate this better than most. In Watchmen, Moore creates a post-modern masterpiece which deconstructs the limitations of both comic books and their heroes. Each chapter borrows from a multitude of styles and genres. Chapter one concludes with a memoir excerpt. Chapter four has bits of a textbook. Chapter seven includes part of the psychological file on Rorschach. Moore, like Joyce, imagined new possibilities for his form. And both authors did so in order to emphasize their particular theme. Joyce wanted to expose the intricacies of the mind, the modes of consciousness, and the typical realist novel failed to prove capable: He combined elements of Greek myth and plundered every work of literature, creating a polyphonic cacophony of styles. Moore, on the other hand, wanted to expose the flaws of the super hero, but the typical comic book wouldn’t do. He needed to put them in the “real world” and rewrote the rules of the form in the process.

Form is as much a matter of technique as it is appearance. And no writer should ignore it.

So concludes our discussion of plot, structure, and form. Stay tuned as next time we will move into the heart of all stories, the very reason we write: theme.

May 13, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

I went to see Age of Ultron the weekend of its release. And even though I was less than excited to see it (more obligated than anything else), I ended up coming out pretty happy about the eleven dollars I had spent. It wasn’t the best film ever but neither was the first Avengers. In fact, I like the second one slightly more. But in my two-and-a-half hours of viewing, and the subsequent hour or two of thought I gave it, did I ever once feel as though the film presented any philosophical message that I found particularly uncouth. In fact, I took part in a podcast that same day, and it wasn’t even an issue that we broched.

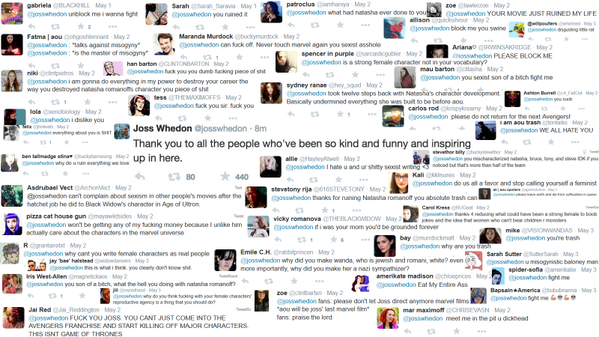

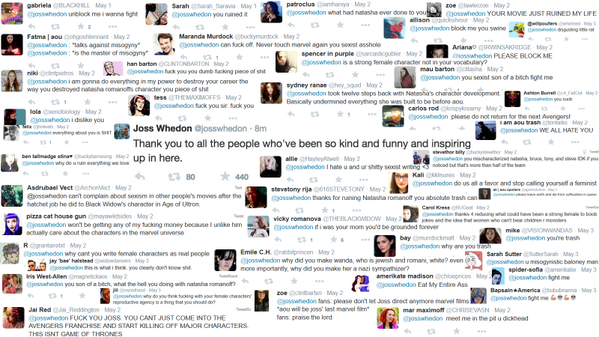

But then along came twitter.

Now whether Whedon left twitter because of these tweets or not isn’t my concern. I’m more so bothered by the pure bile that these people are spewing at an artist whose trying to make something beautiful. And frankly, this is coming from someone who never saw all the fuss over Joss Whedon in the first place. (Yes, I think he has talent: I just don’t think he’s the end all and be all when it comes to witty dialogue.) But why are people so angry? And more importantly, are they right?

Many a spoiler ahead….

One criticism I read came from blastr.com. Two of their critics were discussing Age of Ultron and bemoaned the “forced” relationship between The Hulk and Black Widow. Krystal Clark made the following remark:

“And I’m gonna go there and take a lot of issue with the fact that, in order to make a point for Banner about what being a monster is, they chose to get the one d**n developed female superhero we get in the MCU’s ovaries involved. It’s terrible how Natasha was tinkered with, and a huge decision was taken out of her hands, but wouldn’t it be a lot bolder and more progressive to bypass an antiquated gender bomb like fertility (which, come on, do we even want to touch on that in a superhero tentpole movie?), and just feature a strong, decisive woman like Natasha choosing a super-spy/Avenger life? Because women are so often the girlfriend, wife, mother in every movie out there, you can’t throw in something like a woman not being able to conceive and not have some process it as another thing that Natasha can’t do, instead of focusing on everything she can do.”

This seems to be a problematic analysis of their relationship and the farmhouse scene in general. First, Clark seems to be saying that in order for Banner and Romanov to be able to relate, monster-to-monster, they had to discuss their monstrous details. And according to Clark–and many others–being infurtile is on pare with being a giant green rage monster.

This, I believe, is not the case.

The monstrous side of Black Widow comes not from her inability to have children but from her sins as an assassin, which is shown vaguely in her vision brought on by Scarlet Witch. In order to be a weapon, Black Widow had to be a bad person, had to betray the innocent–much like the Hulk. And that’s the connection, I think, the two make. But when Banner says he can’t have what Hawkeye has (a farmhouse and a wife and three children), Romanov tries to comfort him by saying that she can’t have it either. That’s why it makes sense to jump into a relationship.

Furthermore, Clark asks why does the film have to have this relationship when it could be just Black Widow kicking ass. Now, I know this might sound crazy, but if you spend anytime watching shows or films with bad ass chicks in them, there is often something wrong with that bad ass chick. Just look at a character like Olivia Benson from Law and Order: SVU.

Benson, for a good portion of the series, didn’t get involved in serious relationships. She was a fuck them and leave them kind of woman. Why? Because a woman is tough, she also doesn’t have the ability to love. Of course not, just look at a character like Kima Greggs from The Wire. But that show, unfortunately, is an exception to the rule.

I can think of very few films where a character isn’t involved in a relationship in some way. Look at a movie like Die Hard. John McClane isn’t just a New York cop fighting terrorists: He’s fighting terrorists to save his wife and fix his marriage. But he’s still a bad ass, just a vulnerable bad ass.

How about John Wick? He is defined by his husbandry, devoted to his wife even in death.

All characters worth watching love someone, and Black Widow’s love of the Hulk makes sense. She loves him because he’s not a fighter. It’s something that comes easy to her and everyone around her. She wants someone who’s different. And just because she gave up her ability to have children biologically doesn’t mean she’s a bad woman or a monster. It means she has different priorities. It means she’s happy to be Aunt Nat, not a mother.

And as for Clark’s suggestion that this film turns her in the “girlfriend, wife, mother,” it really doesn’t hold much weight as she seems to get more screen time than Banner. In fact, people are quick to say that she’s become the stereotypical damsel in distress. I guess they missed the twenty minute action sequence where she single-handedly turned the tide of the war against Ultron. I guess they were just supposed to get the Vision back without any trials or tribulations. I guess movies and stories should just be consequence-less.

And of course, who comes to rescue her? Not the Avengers, not even the Hulk, but plain old Bruce Banner. That, I think, says something. It shows growth in his character and hers. He, for once, isn’t the pansy wuss scientist without turning green, and she, for maybe the only time in the series, is vulnerable, needing some help. It doesn’t invalidate her existence. It doesn’t make her weak. It just means she failed–but only for a moment. Once she gets out of her cell, she’s back to ass-kicking. And not only that: She’s saving lives too.

That’s a pretty stark contrast to the woman we see earlier in the film.

Widow goes from someone who takes lives and must carry those sins with her to someone who saves them. That’s why she’s able to go back to the Avengers and work with Captain America to assemble their new squad. She has found meaning in what she’s doing. Sure, she still wants a life with Banner, but it doesn’t define her. This isn’t Bridget Jones’s Diary or Twilight. She’s not that woman who is successful in all avenues except love and feels horrible about it. Those kinds of characters are the worst propaganda as their lives are meaningless without a man. But in Black Widow’s case, it’s icing on the cake. By the movie’s end, she has found some real happiness, even if it is bittersweet.

But of course, if you only spend time analyzing one scene and cherry pick your evidence, I guess it’s easy to complain that a movie is sexist.

May 10, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

A Note on The Text: Due to the nature of the discussion at hand, I felt it was necessary to give a little more care and organization to this post. This is a little less philosophy and a little more nuts and bolts. Also, this, as the title implies, is a large subject that needed two posts to capture its true complexity. Stay tuned, and expect the second half next Sunday.

#

This week’s craft talk is about point of view, which is probably one of the most abused and misunderstood elements of the craft. Some people define it rigidly; others are so careless with it that it seems like it abides by the laws of quantum physics–if it follows any laws at all. While I lean to towards a more rigid definition, those favored by the editors and college literature professors, I think that binaries, in most cases, leave out the necessary naunce that is reality.

#

First and foremost, point of view, for the most part, is, like most elements of storytelling, determined by character. It is part of what helps writers create empathy and an essential part of our reading experience: It is the person whose eyes we looking out of. Typically, there are three major categories of point of view:

- First Person

- Second Person

- Third Person

However, I would also argue we often forget that tense too informs the point of view. And there, of course, three major categories of tense as well:

- Past Tense

- Present Tense

- Future Tense

Let’s start with past tense.

Past Tense

Strangely, this tends to be the neutral default for most writers, and I’m not sure why. Now don’t get me wrong here: I’m not saying that past tense is no good. But it, like every story, every character, every paragraph, every sentence, and every word, should be a conscious choice. Too often are writers afraid to challenge the orthodoxy of fiction, the rules and conventions that we arbitraily follow.

Consider Aristotle’s definition of rhetoric: “It is the ability to observe the available means of persuasion.” It is a very fine definition, but there is one change I recommend: “It is the ability to observe the [best] available means of persuasion.” The choice of past tense should inform the text and theme. The writer should decide on it because there are no better options, not because that’s what everyone else is doing.

So why use past tense?

Let’s take a look at the opening from Carver’s “Neighbors” to find out.

“Bill and Arlene Miller were a happy couple. But now and then they felt they alone among their circle had been passsed by somehow, leaving Bill to attend to his bookkeeping duties and Arlene occupied with secreterial chores. They talked about it sometimes, mostly in comparison with the lives of their neighbors, Harriet and Jim Stone. It seemed to the Millers that the Stones lived a fuller and brighter life.”

Here, Carver uses past tense because it immediately creates doubt in the reader’s mind. When we read that Bill and Arlene “were a happy couple,” it has an entirely different meaning than if Bill and Arlene are a happy couple. Were suggests that they used to be happy, that there now is a problem. In someways, we don’t even need to look at the following sentence to understand that the couple is in crisis. By choosing past tense over all others, Carver can articulate a longing for the past, that great intangible happiness of memory.

Past tense should be decided on because it arouses our sense of nostalgia, of what has been. Readers may not be able to articulate this effect explictly, but they feel it. It is invisibly implicit.

Present Tense

Present tense often gets a bad wrap. People lay down edicts like “Novels should never be written in present tense.” Frankly, I’m not fond of hard and fast rules–especially those proposed without a shred of evidence as to why. I will say present tense can be more difficult to pull off, but just like past tense, if the writer is aware of his or her choice, its rhetorical effect can be alarmingly haunting.

In Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho, he writes almost exclusively in first person, present tense. And though many are quick to label the novel mysogyist and empty, Julian Murphet, the author of the novel’s reader’s guide, gives a compelling analysis of the Ellis’s style that I would be remiss not to mention.

“…American Psycho is a perversely unified text, and the rest of the book…is a carefully considered foil to the violence. Some of the emptiest dialogue ever committed to print; ghastly, endless descriptions of home electronics and men’s grooming products…characters so undefined and interchangable that even they habitually confuse each others’ identities; and a central narrating voice which seems unable and unwilling to raise itself above the literary distinction of an in-flight magazine…. If Ellis wants to bore us, he must have a reason.”

And I am inclined to agree. One of the most obvious effects of the present tense is an otherworldly sense of boredom that it instills in the reader. Just look at these lines from the novel:

“Back at my place I stand over Bethany’s body, sipping a drink contemplatively, studying its condition. Both eyelids are open halfway and her lower teeth look as if they’re jutting out since her lips have been torn–actually bitten–off. Earlier in the day I had sawed off her left arm, which is what finally killed her, and right now I pick it up, holding it by the bone that protudes from where her hand used to be (I have no idea where it is now: the freezer? the closet?), clenching it in my fist like a pipe….”

That might be the coldest description of a murdered woman I have ever read. Add in the lack of figurative language and no voice of reason, and it’s easy to see how people can confuse the novel for one that celebrates the very violence it is actually trying to condemn. Bateman, the narrator and protagonist, does not seem the least bit bothered by this horror. At most, he is thoughtfully voyeuristic; at worst, he is heartlessly removed. The latter seems especially appropriate as his mind drifts to where Bethany’s hand may be. But this wouldn’t be so easily achieved had Ellis used another tense.

Past tense would make it slightly wistful, a serial murderer longing for his glory days (and a form of empathy that I would argue is much more disturbing), but with present tense, it makes the reader question the narrator’s detachment as well as their own. Why should we be so unaffected by such gruesome details? As Murphet puts it, “Bateman’s monologue can…be seen as a ‘corrective’ to literary escapism.” We are given a reality that exists, a reality where brands and pop culture and money are more important and more interesting than the victims that the powerful prey on.

Some people say present tense gives immediacy to the writing, but as we can see above, that isn’t always the case. Often times, people think that the present has a greater sense of now. Yet the truth is it only does the opposite. Just think of how many bad novels begin with prologues told in present tense, while the rest of the book is written in past tense. We mistake in the moment with in media res, but all we end up doing is putting the reader to sleep.

Future Tense

Future tense is the most ignored and undervalued of all our options. It is the conditional, the possible, the imagined, and wished for. It creates an effect that can only be achieved through itself. However, its examples in literature are few and far between, because, most likely, writers are either ignorant of its power or afraid of it. One of the tense’s rare masters was Carlos Fuetnes.

In his novel, The Death of Artemio Cruz, Fuentes uses all the tenses and persons to capture the entirety of the human condition. In the following passage, notice how Fuentes uses future tense to soothe reader and convey an atmosphere of endless possibilities:

“You will close your eyes aware that the lids are not opaque, that though they are folded down, light still reaches your retinas, light of the sun that will remain framed in the open window at the height of your closed eyes that, being closed, blur all details of vision, altering shadow and color without eliminating vision itself; the same light of the brass penny that will spend itself toward the west. You will close your eyes and you will see again, but you will see only what your brain wants you to see: more than the world, yet less: you will close your eyes and the real world will no longer compete with the world of your imagination.”

Notice that Fuentes uses repetition and winding, lengthy sentences to enhance that effect. We delight, as the protagonist delights, in the what may be: a discovery outside ourselves and inside ourselves.

Future tense may not be sustainable at great lengths, but when dealing with the possible, it should be a choice closely considered.

#

And so concludes the first half of our discussion on point of view. Even though the tense we use may not seem important at first glance, it is nonetheless an important choice which decides the tenor of our fiction, something so invisible its power goes unnoticed. Next week, we will look at the potential points of view available to us and how and why we should use them. Until next time….

May 6, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

This guest post comes from Michael Aronovitz, a friend and colleague who specializes in writing horror. Here he reflects on the nature of horror and what it is that attracts him to the genre. Though my fiction rarely moves outside the literary realm, I have always admired and respected those authors who could tell stories through conventions while at the same time finding ways to subvert them. Michael, I believe, is one of those rare talents. I hope that in the future I can find other genre masters who can provide the clarity and insight I cannot.

###

I am often asked why I write horror fiction, and my answer is that it’s complicated. In terms of fundamentals, I believe that all fiction is based on at least some measure of horror and darkness, as stories without impending perils don’t publish. Consider the super-criminal holding a .32 Beretta to the head of a powerful C.E.O’s best friend sitting next to him, after killing the guy’s head broker two chairs down and saying, “What’s the code? Or do I keep shooting until I get to someone you care about?” (Action/Crime). Is there all that much intrinsic, baseboard difference when Cinderella has to leave by 12:00 or her dress turns to rags, leaving in heavy sub-text that “home” equals familial abuse (Fairy Tale), or that Anastasia Steele considers signing a contract with her new boyfriend, permitting him to go beyond “vanilla sex” and abuse her in his sick little spank-chamber (Romance/Erotica), or that some serial killer in the suburbs of Ohio is “skinning his humps” (Thriller)? Each piece of fiction that inevitably sells contains something in the story-action with a measure of consequence, through which a character must ask the question, “If I don’t do this, I must prepare for something to happen that will hurt me, or make me feel bad, or affect a loved one, or cause harm or death. Therefore, in order to prevent ‘this’ I must do ‘that.’”

If I don’t ask her to the prom by the end of 4th period, she’ll wind up going with Biff.

If I don’t clamp down more on my 16 year old daughter’s latest habits of staying out late with that monster of a boyfriend, she’ll end up beaten and pregnant.

If I don’t marry soon, I’ll wind up an old maid.

If you call the police, I will kill a school teacher in Westville. If you do not call the police, I will kill an elderly librarian in Jackson County.

I do not see such heavy contrast. That being said, I do believe that there is a schlock label affixed to horror, because we immediately associate with it the old fashioned archetypes: zombie, werewolf, water beast, mummy, witch, warlock, and vampire, those so familiar (and parodied) that they ring of “comic book” and youth and fourteen year olds listening to heavy metal, painting their nails black. There is also the paradoxical stigma that if a horror story doesn’t scare the reader, it has failed in some way, yet if it does frighten the reader it is gimmick-oriented. Aside from the clear argument we would make against the former issue, recognizing the popularity of cable television horror like True Blood, The Walking Dead, and Penny Dreadful, I would argue that first, horror no more has to scare a reader or viewer than good comedy is meant to have us slap our knees and guffaw out loud. And it is not any sort of “gimmick” that attracts most horror readers. Pay-offs are cheap if they depend on splatter, and most horror writers would attest to the fact that their foreshadowing and character oriented epiphanies are far more important than blood flow.

Of course, violence-exposed is a part of the genre, and I will be the first to admit that I have a stable of physicians I communicate with when I need to find out how much blood will spray in what manner in a variety circumstances. I suppose the point is that a good romance doesn’t make us turn the page because the five paragraphs of graphic erotica in chapter 19 were well delivered. We all (or most of us at least) know how the moving parts work. The work sold because there was something at stake and we believed the characters enough to visualize them. And while we are on the subject, it is not the raw humping and pumping that sells even the fuck scenes. It is the story around them and the discomfort leading up and during that entices us, the teasing, the uncertainty, the misconceptions, the foreplay. Same with good horror. The killer car in Christine by Stephen King is not finally the point, hell, it’s not even important. It is the slow destruction of the child in Arnie Cunningham (and what grows in its place) that hooks us.

On a more personal level, I am often mystified by some reactions to my own fiction. I often have “non-horror” people jerk away from it, often like old fogies at a P.T.A. meeting, trying to discuss whether or not a well written piece of pornography is in fact, well written. On the other side of things, many critics of horror say that I’m not really a horror writer. Why? Because I don’t write “horror.” My favorite “horror” writers don’t write it either. They write “fiction.” There is a rise to climax where a protagonist of some kind has his or her face-off with an antagonist. The ending could be all sunshine and roses, but if anything, horror endings are often untethered.

So I write tragedy.

So happy endings read odd to me.

So I slow down and look at car accidents.

In the end, I will inevitably put a book down no matter what “genre” is tacked to it, if the thing begins with “It was a day like any other day,” or “Josie was bored.” She was? Well, so am I. If that makes me a horror guy, it makes me a horror guy. I appreciate peril. I suppose the biggest difference is that in the scenario where “Melvin” wants to ask “Barbie” to the prom before “Biff Malibu” beats him to the punch, I am far more interested if Melvin goes to the maintenance closet where he’s hidden a dozen roses, and there’s a ghoul waiting for him behind the mops and floor polishers.

###

Michael Aronovitz published his first collection titled Seven Deadly Pleasures through Hippocampus Press in 2009. His first novel, Alice Walks, came out in a hardcover edition by Centipede Press in 2013, and Dark Renaissance Books published the paperback version in 2014. Aronovitz’s second collection, The Voices in Our Heads, was published by Horrified Press in 2014, and The Witch of the Wood came out through Hippocampus Press in early 2015. Aronovitz’s first young adult novel, Becky’s Kiss, will be appearing through Vinspire Press in the fall of 2015 and his third hard-core adult horror novel titled Phantom Effect will be published by Night Shade Books in the fall of 2015. Michael Aronovitz is a college professor of English and lives with his wife and son in Wynnewood, Pennsylvania.

For more information about Michael and his work, check out his blog.

May 2, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

In order to talk about character, we have to talk about why we read in the first place. It’s a good question. Why after some 2000 years are we still reading Homer? Who cares about Vergil and Ovid? Why go to the library to check out La Divina Comedia? Why study Shakespeare? They’re all long dead, but surely reputation and the bidding of schoolmarms and ancient professors has something to do with it. But what about more recent shit, like Tolstoy or Turgenev, Woolf or Wilder, Burroghs or Beckett, Morrison or McCarthy, Egan or Eggers? Most books, nowadays, have a Wikipedia page or an in-depth chapter-by-chapter synopsis on Sparknotes. If you want to know what happens, you’re only one google search away. And better yet, why do I keep re-reading Dubliners when I have shelves of unread novels in my bedroom?

I can tell you it’s not because we need to know what happens next.

#

A few years ago, I was having coffee with Bob Mooney, my thesis advisor and writing mentor. Bob is the kind of guy, who, even when you’re with him, seems somewhere else, and his heavy grey face and disheveled hair made that distractedness obvious from across the street. But Bob had learned from masters like John Gardner and had Sunday dinners with the people I had studied in college. (Once he told me he had to hang up because Jack Barth was coming over. Only after did I realize he was referring to John–fucking Sot-Weed Factor–Barth.)

We bullshited for a while, little things about who had read my manuscript and what my writing process was like. It didn’t take long for him to get to what he had probably been thinking about since we agreed to meet. He wanted to know why my narrator had felt so bad for such a scumbag character.

I told him, “I always write about people I hate.”

#

Until my sophomore year of college, I had never heard of Alex Jones. My boss at UPS thought he was the Second Coming. She said that he revealed the truth behind 9/11; I thought the truth had already been exposed in over 1000 pages by the 9/11 Commission. (I’m sorry, but I have to take a moment to comment on the stupidity of 9/11 Truthers. Really, what kind of cover-up could be that fucking massive? Who says, yeah, a bunch of people wrote a detailed report that’s pretty Goddamn authorative just to keep the sheep in the dark?) Needless to say, I went home and watched some of his documentaries out of curiosity, and after an hour of rambling, I knew he was crazy. But even though I thought he was manipulative and dangerous, I strangely felt bad for him too. I knew he believed every word he spoke, even if his evidence was filmsy and his points were illogical. He was passionate, whole-heartedly invested in his cause, and that was something I understood.

I knew I wanted to be a writer back in high school when I was skipping pep rallies to write poetry and staying up late to watch movies and play video games but convinced I was going to be a physicist. It was only after I failed physics freshman year that I had the courage to admit it. So I felt bad for Alex Jones because I imagined what it would be like if everything I stood for turned out to be wrong. And the worst part: he’d never have a chance to see outside himself to know how deluded he is.

That’s what fiction is for: It’s an opportunity to doubt, to dream, to love, to feel through the eyes of another. The scholars might say it gives us insight into the human condition. I call it empathy. But how do you establish empathy through character?

#

Joyce is a figure both revered and reviled in the literary world, and if you’ve had a chance to read him, it’s impossible not to form an opinion one way or the other. I fall into the former camp.

His character and alter-ego, Stephen Dedalus, is probably his most well-known creation and serves as a model we should all aspire to. Stephen’s essence, his soul, is his ambition, his desire to become an artist–something he takes very seriously. He wants to be a great Irish poet, and it informs every aspect of his life. But just like Luke Skywalker or Odysessus, there are roadblocks that make his journey difficult. Stephen is torn between his ambition and his family, his country, and Catholicism. Of course, by the novel’s end (SPOILER!), he does what he needs to, but even if we didn’t take the time to read A Portait of the Artist as a Young Man, we would could see it in his name alone.

He is Stephen after St. Stephen, the first martyr who was stoned to death for blasphemy. This is, by no means, a mistake or happy accident. It suggests Stephen Dedalus’s own “martyrdom” and “blasphemy”: his sacrifice of his family, his suffering at the hands of the Church and Irish and English society, the “death” of his religious life, and his radical views on art and sexuality. His last name, Dedalus, is an obvious reference to the Greek mythological figure Daedalus, an innovator, a mature, skilled craftsman, an artist of the highest ambition. Stephen’s very name reflects who he is and tells his story. His growth as a character is established in two words.

Of course, this is shown through his choices as well. Even though Stephen is a pussy who “wouldn’t bust a grape in a fruit fight” (that might be Jay-Z and not Joyce), when it comes to art, he does not back down. In chapter two, Heron asks Stephen who is the greatest poet, and Stephen replies, “Tennyson a poet! Why he’s only a rhymester…. Byron [is the greatest].” Stephen is so committed to his cause, he can’t even keep his mouth shut. He doesn’t care that everyone else thinks that Byron is “only a poet for uneducated people,” that he was “a heretic and immoral too.” He’s an artist, and he knows it. It’s only by the novel’s end that he gathers the courage to admit it to himself: “Old father, old artificer, stand me now and ever in good stead.” His focus is singular and every moment in the novel demonstrates his movement towards the truth of who he is and his acceptance.

#

A lot of people advise young writers to start with a list of attributes: name, age, height, occupation, what they ate for breakfast. If that kind of stuff can tell you who and what a person is, then the Census Bureau should be writing better stories than all of us. These things can’t be forced on a character: They are chosen by them.

Philosophers like Aristotle believed that essence precedes existence, that the soul exists long before the physical body. Even though I agree with Sartre, that, I think, is where you need to start when writing characters: What kind of man or woman are they? Most people think of themselves as the hero of their own story. They are always trying to do the right thing. Sure, there are limits and compromises, but how far they’ll go and by what means is determined by the character’s soul, the heart of who they are. The writer’s job is to put them into situations which test it.

A character’s essence must infect every part of their being, from head to toe. It may evolve and change and refine itself through struggle, but the core remains and determines their every choice, every success and every mistake. That’s what allows us to empathize with Nathan Zuckerman or Dr. Manhattan, not backstory and exposition and interior dialogue. Nobody cares where you’re from or what happened to you when you twelve years old. That’s all window dressing. It’s when those little details tell a story of your choices, when they serve as evidence of who you are: That’s what makes the reader turn the page.

April 29, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

Lately, there’s been a lot of talk about the experiences of people of color in MFA programs. First, there was Junot Diaz’s piece at the New Yorker last year. And just recently, David Mura wrote up an essay on Gulf Coast‘s blog. Both of them describe their experiences as people of color in the MFA hegemony, and I have no doubt that their frustration is real. There are a lot of white people in MFA programs, and it can be alienating I’m sure. (We only had one person of color in my MFA cohort and only a handful of professors of color, and I cannot say how they did or did not feel. I did notice that race was rarely discussed but only because it seemed that the white people tended to write about white people and the people of color tended to write about people of color. I did not feel, fortunately, if it was brought up, that it would not be ignored or trivialized.) But in both articles, there seemed to be an underlining idea, one that made me somewhat uncomfortable as an artist. They suggested that writers have a certain responsiblity to depict their reality, which I agree with, but that comes with a caveat: that a writer’s reailty should consider the reality of others.

And this got me thinking.

#

In Mura’s article, “Student of Color in the Typical MFA Program,” he says that a lot of white people are ignorant to this topic of race, unwilling to discuss the ways they consciously and unconsciously uphold white supremacy in their fiction. He writes:

If and when the student of color voices her objections to the piece, more often than not, neither the white professor nor the other white students will respond to the actual critique; nor will they inquire further into why the student of color is making that critique.

They disregard this opportunity to discover their own whiteness, to investigate why a particular character is a stereotype, and potentially, right the problem. I think these are all fine ideas worth exploring. (I am, after all, Italian-American and, therefore, bleed marinara.) But there’s an implicit assumption, if the writing workshop recognizes and discusses and agrees upon this attempt to fix things in their stories, that I find problematic: Artists, with a little help from others, can fully control their message and its effects on the individual reader.

#

A few years ago, I was reading an article in College English by Gay Wilentz. It claimed that The Sun Also Rises was an anti-Semitic work, conveying the nation’s anxiety over the Jewish usurper. The author gave many examples and laid out her case as best she could, but it was something I didn’t buy. The novel seemed so much more complex than that. Sure, there were a lot of characters who hated Robert Cohn because he was Jewish, but I wasn’t sure if the novel necessarily endorsed that type of behavior. After all, Jake Barnes’s opening narration presents Cohn as a somewhat tragic figure. Barnes describes him as “very shy and a thoroughly nice boy,” who “never fought except in the gym.” He even tells us that the reason Cohn took up boxing in the first place is “to counteract the feeling of inferiority and shyness he felt on being treated like a Jew at Princeton.” If the novel is trying paint Cohn as a Jewish stereotype, it doesn’t seem to be very successful. Even later, when Barnes goes fishing with Bill, Bill asks him to say something pitiful. Barnes answers, “Robert Cohn.” That seems to run contrary to this idea of Cohn as the Jewish boogeyman. And furthermore, while the rest of the cast are quick to call Cohn a “kike,” Barnes, as far as I can remember, never utters the word himself. But instead of recognizing these points of contention, the critic ignored them: They weren’t relevant to her data set.

She had an argument, and she was going to prove it.

Most people would ask what was Hemingway’s point? They might even wish to summon the author through séance and ask him his reasoning, but I feel this too wouldn’t be very valuable. Why should we worship Hemingway’s analysis? He’s not God of the text, just the vehicle from which it came out. There’s a complexity there, and it’s not easy to say exactly what it is or is not.

And it’s not just in literature that I see this either. Tyler Shields, a photographer did a photo shoot with Glee cast member Heather Morris.

A few people said that these photos glamorize domestic violence, and the photographer himself later issued an apology. Now let’s actually look at some interpretations of these photographs.

In the first photo, the woman, who has a black eye, is restrained by the iron. She clamps down on the cord to bite it. She is dressed like a 50s housewife. The first way we can perceive the image is that it is a sexualized fantasy, depicting what some wife beaters probably masturbate to. But personally, that’s a little simplistic. She’s restrained because she’s bonded to domesticity, a burden the iron represents. Her husband, most likely, gave her that black eye. But the fact that she’s biting through the cord suggests resistance, the desire for escape. And if we look at the next photo, where she places the iron over the man’s crotch and smiles, there seems to be another message, and that’s one of empowerment. I’m not saying these are the only interpretations. And none are superior. But there does seem to be a problem with saying that because one of these interpretations angers us, that is no longer valuable or useful. It’s art, and it isn’t designed to have a specific, concrete meaning. That’s the beauty of it, the–as the deconstructionists would put–undecidability of it.

So why does the artist need to apologize? Should Shields have foreseen this possible consequence? And if he did, how could he correct it? There’s no doubt a meaning Shields perceives as viewer himself (not that his is the “correct” one). But let’s say someone mentioned this possible interpretation, and he reshoots. Won’t there be another argument against him–somewhere? Isn’t there something which will always rub someone the wrong way?

#

Roland Barthes, in his book Image, Text, Music, wrote: “To give an Author to a text is to impose upon that text a stop clause, to furnish it with a final signification, to close the writing.”

It seems like giving a text a critic does the same thing.

We assume that because the author has summoned the work into existence that he or she is God, but if we fool ourselves into believing this, then there is no further cause for investigation. But if we say that because an interpretation is valid and that interpretation evidences a message we disagree with, then the work must be condemned and extinguished, unworthy of appreciation or discussion.

But I think this too starts with the wrong supposition.

Art is an act of creation, not just on the behalf of the creator, but the individual viewer too. It is an act of two halves of the same soul coming together to create meaning, and that meaning exists uniquely between each reader and each author. If we impose our flawed and cherry-picked readings on all others–and the author–we do all art a disservice.

#

I was so excited my junior year of college. I had known I wanted to be a writer from the moment I failed physics my freshman year, and I was finally getting a chance to take a class in creative writing.

My excitement quickly subsided as I realized that I was the only person who actually wanted a career as an author. Everyone else, it seemed, took the class as an easy elective. Nonetheless, I persisted regardless, scribbling voluminous notes on people’s manuscripts that they tossed in the trash after class.

We spent the first half of the semester writing poetry, and in that time, I wrote two bland poems. One was an image poem; the other was about consumerism–or something like that. They were not very good poems, but I had little interest in writing poetry. I wanted to be a novelist.

I read anything I could get my hands on. I explored the Canon, read as many books off as many great novels lists as I could find, burned through the recent National Book Award and Pulitzer winners (including Diaz’s Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, which I loved). I spent afternoons in the library, and in the evenings, after work, I paged through Wikipedia trying to pick up every bit of literary history there was. I also was particularly fond of Bret Easton Ellis.

One of our first fiction workshops showcased one of my peers and me. I couldn’t wait to learn what the weaknesses were in my writing, places where the pacing sagged, where characters motivations were unclear, where the style could be sharper. I longed to learn the craft, the necessary elements in telling a story. All I had to go on, at that point, was what I picked up from the great fiction I had read and a few articles I had read online. I couldn’t wait to have it all explained by an expert.