July 8, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

Truth be told, I’m not very familiar with the work of either Matthew Doffus or The Buffalo Almanack. The most I could find about the former was a poem he had published in Barrelhouse, and as for the latter, the most I can say is that I submitted to them once in the past. But that’s about all I know, and frankly, I prefer to keep it that way–at least, for now. I can’t even tell you how much the magazine awards the winner of their Inkslinger contest. But I’m trying to stay purposely ignorant, with as few biases as possible, and bring you an honest critique of the story.

“Shadowboxing” follows the life, career, and death of artist Sara Frye as seen through the eyes of her sister Anita. The story deals with themes of mental illness, youth, and artistic integrity. The most obvious and abundant strength of the story is the prose. For example, when the older sister Anita, visits Sara after her first suicide attempt, Doffus writes:

Back at the hospital, she flapped her bandaged arms at me and called me Auntie, as though nothing unusual had transpired. Dark circles ringed her eyes like bruises, and her normally pale skin looked translucent. She’d lost weight: her collarbones and sternum stood out beneath her gown. Her blond hair, shoulder-length when she’d colored it with markers years earlier, had been hacked into a lopsided bowl cut that called attention to her pointy ears.

The prose has a clarity and beauty that is rare even among literary writers. Although a simple description, Doffus seeks out le mot juste and paints a striking image in the fewest words possible. Furthermore, the sentences, aside from being lean and muscular, don’t necessarily draw attention to themselves. He’s not attempting to push his sentences to the breaking point or trying to be as elliptical as possible. Neither choice seems particularly important to the author, not that I think that those moves would improve the story. As I said, his prose is simple–but recognize that it isn’t simplistic. Just because most sentences are variations of the typical noun-verb construction does not limit the writing. It still has a clear and distinct rhythm and never once does it feel like a chore to move from sentence to sentence. Doffus adds enough variety with introductory prepositional phrases, complex, compound, compound-complex sentences, and appositives that his prose has a momentum that beckons the reader to read on. His descriptions are probably the best part of the story.

Surprisingly, the peripheral characters are well-developed too. Lines like, when Sara marries a fellow artist and brings him home to the family, “For the rest of [Anita and Sara’s parents] lives, they couldn’t understand Ravi’s stuffy, conservative suits were an artist’s affectation, not a sign that he was a member of the Nation of Islam” tell us a lot about the the parents without wasting the reader’s time. And though Sara seems little more than a manic-pixie dream girl taken to her logical end (which I will get to later), Anita, our narrator, is particularly interesting, as the first thing we learn about her after her sister’s death is that Ravi tells her not to make the suicide about Anita. However, this idea never seems to be followed up. In fact, this missed opportunity leads to the story’s overall problem: the structure and story itself.

The tale begins as Anita tells us that she had learned of her sister’s death via the internet. She says, “Like much of what was written about her, the post made up for a lack of facts with innuendo and attitude.” Yet, this idea never seems capitalized on either. There’s no real contrast of the woman the rest of the world sees and the one her sister sees, at least not in a meaningful way. Most of the story looks at things through Anita’s eyes, her private encounters with her sister. While we do have hints and reports of what the rest of the world thinks, like the French critic who labels her elfe terrible or the journalists asking questions about her at the end or the many awards and honors that Sara has been bestowed, there is an obvious missed opportunity here. If, from the outset, we’re promised a juxtaposition of who Sara was and who people thought she was in the Charles Foster Kane-mold, why is it we’re so often sidetracked? It seems like this part of Sara’s character isn’t fully realized, as though the writer didn’t know the answers himself. Yes, people think she’s brilliant and genius, but what else? That outside portrait of Sara is sorely lacking here. And Anita’s experience shows her as mostly irrational and crazy, but that, at least, has some depth to it because it is shown in scene.

Later on in the story, there’s a dispute between Ravi and Sara, an argument over a painting which he stole from her and passes off his own. This feels more like a distraction than anything else, a plot point arbitrarily thrown into the mix rather than thoughtfully considered. It might be possible to say that the theme of perception could be paralleled with Sara’s public/private image and Ravi’s theft, but again, the writer doesn’t really emphasize this. It feels as though the story doesn’t know what it wants to be. Is it a about who we are and who others think we are or is it about jealously in the artistic world (Sara’s second and successful suicide attempt comes after her estranged husband wins a MacArthur Grant)? Both of these ideas could have served as stories of their own, but here it only causes cognitive dissonance. Even Doffus’s choice of scenes and character interaction, while strikingly realistic, feel wedged into the story instead of arising naturally from a causal series of events. The first scene we get is of Sara as a child, when she gets a Polaroid camera. We get some nice summary, essentially a series of snapshots, that flesh out the character and show her eccentricities, but when the scene starts the conversation is banal and directionless.

Sara tells her sister about why she hangs her Polaroids with nails, “Thumb tacks won’t work…so I use nails.”

Anita replies, “How does Mother feel about this?”

“She made me promise not to hit my thumb…. Like I’d do that on purpose. That’s why they call them accidents.”

These first lines of dialogue should be of extreme importance, but instead, they only add to our confusion. If we fold them into the theme and overall plot, we have to ask, “Are we to question Sara’s death?” Was it an accident? Putting a gun in your mouth seems like a strange accident. Is it to show how Sara has changed by the story’s end? But I would argue Sara doesn’t undergo any change. She has superficial ones but not ones that matter. She’s a manic-pixie dream girl through and through from start to finish. There really isn’t any character here who makes a change, not even Anita. This is what I think does the story in. The prose is wonderful and the characters are interesting and their conversations and thoughts feel meaningful but that meaning is lost on the reader, presumably because the writer was just as unsure himself.

In short, though there are some nice things here and everything here feels cohesive and unified, it ultimately falls apart under careful scrutiny. It’s worth your time if you want a quick and enjoyable read, but overall, it’s a story that’s not worth the analysis because you’ll end up getting frustrated by the ill-defined themes and one-dimensional nature of the protagonist.

June 19, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

Let’s be honest: I’m one bitter bastard. I got into this game because I wanted to write great fiction, because I wanted to reinvent the literary discourse while, at the same time, nodding my head to those great masters who cemented the tradition and inspired me in the first place; however, the further I get along (and the more I read), the more often I find myself frustrated and alone. When I was in grad school, I didn’t find too many people who shared that dream. There were some, of course, but most seemed content to write because they liked it, which is a fine reason to do it. A few were interested in money and were the most indignant when it came to used books. (These people I found to be the most insufferable. If you’re upset that consumers want to buy your book for less, it does not mean they are bad people or they are purposely fucking you. You indebted yourself to a monopolistic corporation in order to reach a larger audience: Get over it or negotate a bigger advance.) But probably most upsetting were those who had no connection to the tradition, no real knowledge of literature, and no real talent. These students tended to be the ones who left with books deals and agents. And this is something, I think, is endemic to the MFA hedgemony. Writers are pushed into the wild without real training or skill, and they, in turn, help to shape the literary discourse in their own image, which marginalizes quality fiction.

#

I read an excerpt from a novel that was getting a lot of press and praise at the time. It was in Narrative, and I haven’t really heard much about the novel or the author since then. But I read it without expectation. It told the story a young woman who goes to a party, discovers it’s kind of a lesbian orgy, goes home, and then realizes she’s in love with a woman from the party.

Most of the dialogue is banal and useless: “Patsy must have spotted you, the pale woman said now. Iris smiled. I’m Sylvia, the woman said. Iris, Iris said.”

When you’re writing, you have the ability to go anywhere and show anything. So why the hell did this author choose to waste ten seconds of my time? How about a sense of conflict? But in this excerpt, that problem is buried.

Iris put her hand to her hair to fix it, and the dwarf with the white fez came by. Champagne? he said. Oh, please, Iris said. Rose looked at her. Well, here I am thinking, Look at this little bumpkin, and here you are, having your way with Armand and who knows what else. Shame on me, she said. Oyster? Iris opened her mouth.

This was not the kind of party where you said, Oh, I’ve never eaten oysters, or, Oh, gosh, they look wet and disgusting, which they really did. If oysters were the path to parties like these and beautiful, dazzling, dark Rose Sawyer, Iris thought she could toss back oysters like cold beer on a summer day. She managed two and chased them with champagne.

Iris clearly has never had an experience like this, and that’s where the problem lays. But she doesn’t seem to be doing little more than observing. Instead, the author emphasizes description over character and reaction:

“Who should lead?” Rose said.

“I could,” Iris said quietly.

“But you don’t want to,” Rose said, and she put a strong arm around Iris’s waist. All Iris’s dancing, her show routines, waltzing with her father, the senior-year parties with Harry Bledsoe and Jim Cummings, who were the best dancers in Windsor, faded away. She was dancing for the first time, right now, her face against Rose’s smooth, powdered cheek. Breast to red silk breast, thigh to black silk thigh. They did two promenades and a slow twist, as if they’d been practicing, and Rose pulled Iris back to the divan. More champagne appeared.

Again, we get very little in the way of conflict or anything interesting. The character, in this excerpt, is so unwilling to do anything more than observe and hold momentary, somewhat thematically relevant conversations. Why isn’t she doing something? Just because she’s scared or beguiled or lost doesn’t mean Iris should be useless. She has choices to make, more interesting choices with actual stakes attached, not a dishonest twist to generate interest after your reader has fallen asleep. But the writer doesn’t seem interested in telling a compelling story or even creating an character we care about or want to know about: The writer is, like most players in literary fiction, too concerned with crafting gorgeous prose and not what it expresses.

And though this may not be indictative of the work as a whole, you’d think an excerpt in an important magazine like Narrative would be one, complete and two, interesting. But instead, we’re given tedium and useless description, two things readers tend to skip.

This is why literary fiction can’t find broad appeal.

#

It’s pretty easy to identify the problem when it presents itself on the page, but it’s a little more difficult to look at that same problem and cite it institutionally. If literary fiction’s greatest threat manifests itself through boredom, the question arises: Why? The answer, I believe, is surprisingly simple. We have the blind leading the blind. Few writers running, publishing, or submitting to the big, little magazines these days have mastered the form. They rely on instinct and intuition. They write, edit, and decide with their gut. They don’t seem to have a set of objective criteria that determines good writing, and if they do, there is but one consideration: the prose. These editors and writers are the most disappointing of all. They spent their early years reciting Virginia Woolf and lines of poetry but never truly took the time to discern what made that prose better than others. These writers are quick to object to theory and rhetoric. They don’t like definitions or structures. They merely listen. Does it sound right? Often times, the work they produce or publish is little more than a fragment, an ancedote, inconsequential, not at all a story.

I too grew up loving the music of language (and I still find sentences or images that make me stop reading and write the words on my thigh with a finger), but I’m not foolish enough to say that is the sole criterion on which to judge. Good sentences are a given. They should not be considered special. A writer with sloppy prose is not worth reading regardless, and a writer with masterful prose and nothing to say is even worse.

Many of these writers eschew the tradition. They claim that form is limiting, that they need the freedom of a true artist. But if you have yet to learn the basics, what do you really have to deconstruct? How can you experiment with something you don’t fully understand? The budding bodybuilder does not start with drop sets and complexes: They learn the movement first. And can we really say that artists are hamstringed by their own ever-expanding knowledge? Does the musician suffer because he learns scales and modes? Is the painter stifled when she practices composition? I think not; in fact, that mastery most likely enhances their abilities. Yet, rarely, except with genre writers or writers for the screen, do I hear anyone talk about the governing laws of story. All great artists honed their craft. They emulated their forebearers. They practiced.

Hunter S. Thompson famously wrote out sentences from The Great Gatsby. Ben Franklin memorized articles from The Spectator. Joyce said he was content to go down in history as a scissors and paste man. But they didn’t just learn to write sentences. They discovered how a work was constructed. They processed the elements that comprised its composition. They taught themselves to search for le mot juste and the best available means of persuasion. They perfected the form before they destroyed it.

#

One of the most obnoxious trends in recent years is the rise of flash fiction. Editors have propped it up, thinking it “competes” with Facebook and video games and television. (It doesn’t. They’re entirely different media.) Because of its brevity, flash fiction, usually under 1000 words, can be finished before you put away your dick after a piss, but, in most cases, I would not describe it as a satisfying experience. At its best, it is a first paragraph or ten from an otherwise incomplete story.

Here’s an example from Tin House’s Flash Fridays.

The story, titled “The Girls Where You Live,” relates the uninteresting tale of a young man (our narrator) who meets up with a homeless guy who tells the narrator to “not eat the pussy.” The narrator trades the homeless man two cigarettes for seventy-five cents. The author then follows:

I was drunk. We were all drunk it seemed. Everyone I knew. We drank until we felt like copies of ourselves, which would vanish, and whatever plans we’d made too, in the morning’s first blue light. I saw the man, and the cashier and the store, which was plastered, ceiling to linoleum, with liquor, beer, cigarette, and cigarillo adverts in bleary swathes of imagery, as through a fogged window polished with your hand. And in the corner near the door, there was a coin-operated candy machine half-full with jellybeans, except where were the children? Where were the mothers who’d dug through their purses and found one last quarter?

“That’s not very gentlemanly,” I managed.

In a story of less than 1000 words, this author, who is somehow or another an MFA candidate at Johns Hopkins, wastes the reader’s time with an expositional onslaught of pseudo-philosophy. And our conflict? He mildly disagrees with the homeless man.

This is followed by some questions about where the narrator is from, and the narrator answers that there were many pretty girls in his hometown. They converse about the girls’s hygiene, and the story ends with:

“I’ve met kids like you, you know. “ He said, “I’ll bet your mamma traded you silver dollars for your baby teeth, didn’t she? I bet she smelled all over just like the palm of her hand. When I lost a tooth, when I put it beneath my pillow, do you know what I found in the morning? I found a tooth. And there was still a bit of blood on it. And it was mine. And I buried it in the yard like a dog.” He laughed madly again, which shook the whole of him and rattled his eyes.

I left him there, laughing and gasping, and hocking loogies into the stormdrain.

What? I’ve offered a large portion of the story here, but even if I wasn’t so curt in my description, I doubt you’d have any better understanding of this than I do. Just what the fuck did I read? I get that the author believes he’s highlighted something profound, something about class, but I just don’t see it. This might be amusing if you still get a chuckle from hearing about pussy. (I’ve had sex, and I’m over the giggles. Thanks.) Otherwise, what’s the point? There’s very little sense of conflict here. The description is a vehicle only for itself. The dialogue doesn’t advance the narrative (if anything, it delays it). And the characters seem poorly drawn and one dimensional. Where’s the arc? Where’s the plot? Where is any evidence of craftsmanship?

Of course, this is no mere aberration. Here’s one from McSweeney’s Quarterly, called “Don’t Get Distracted.”

It begins, “One morning in January, I was walking to my studio feeling happy because I had spent the night with a new lover. I passed a mother and father carrying a baby…. A man walking in front of me turned around and said that it must be the couple’s first baby, because otherwise they would have covered its head….”

The first sentence is mostly forgettable. Why does this story start with “Everything is great.” Characters whose lives are perfect are boring. Then some insignificant man says something significant. (This seems to be a popular trope in shit fiction.)

Our narrator and the man walk together and converse, and he tells her, “Ladies must always walk on the inside.”

Our narrator asks why, and the man responds, “Ladies must walk on the inside because if they walk on the outside, it means that they’re for sale. If a man says he loves you, pay attention to which side of the sidewalk he lets you walk on.”

She thanks him for walking her home and the conversation, and he tells her, “Remember, don’t get distracted.”

And the story ends with her reply, “I’ll try not to.”

Seriously? Seriously? Fuck you.

Again, there isn’t much more to that story than what I offer here. How is this publishable? How is this quality work? Who does this appeal to? It’s banal. It’s trivial. It’s not interesting. The theme here, about what men do for their women, isn’t explored at all. Does the narrator fall in love with the man she’s walking with? Does she reconsider her relationship with her new lover? Does she realize that she loves her lover? I don’t fucking know. You know why?–because it’s fucking hidden. What is this, a goddamn scavenger hunt? There’s not enough detail to make analysis worthwhile. The author doesn’t seem aware of plot or structure. The author doesn’t use the best available means of persuasion. The author doesn’t even seem to recognize that a theme without context or clarity is no theme at all. And while we have a symbol in the form of the sidewalk, it doesn’t help if that symbol doesn’t illuminate anything nor is its meaning explained.

And just one more example of the “short-short story,” which is apocryphally attributed to Hemingway: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.”

First, if Hemingway did write this, it’s by far one of his worst, and lacks the brilliance of his stories like “Hills Like White Elephants” or “The Short, Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” Second, this isn’t a story. It might be the beginning of a story, but it’s certainly not a complete one. What is the status quo? Fuck if I know. What is the inciting incident? Baby dies? What is the debate and break into act two? Who knows? The midpoint? Suck a dick. The third act twist? Fuck off. The climax and resolution? Somebody is poor.

Wow, I am blown away.

Who are my protagonist and antagonist?

What is the point of view?

What is the conflict?

What is the setting?

Are there symbols?

What is the theme?

I know I may seem like the crotchety old man here, but flash fiction is not a great innovation in storytelling. It’s not subverting the form for any clear purpose. It doesn’t change the short fiction form because of its limitations. And it is certainly not learning vaulable lessons from the micro content we find on the web. I’m not saying that YouTube and Twitter can’t be inspirations or help to mold the form–they can–but if all we’re getting out of those models is that people like things short, we’re not asking the right questions.

#

If there is one writer who offered more formal innovation than any other to English writing, it must be James Joyce. In one book, he invented and reinvented English prose and style. Ulysses is a towering momument of the possibilities of literature, the same way Watchmen is to comics or The Odyssey is to epics. But the novel took Joyce seven years to write. He mined every form of media to make an enormous compendium of forms, which still adhered to the conventions of story and the novel. (If you deconstruct it, you will still find all the necessary elements of story.) Of course, he was forty years old when he wrote it.

But let’s go back a few years, before he was a God of English prose, when he was still finding his way as an artist. Whenever people talk about Dubliners, they usually bring up one of two stories: “Araby” and “The Dead,” two master works in the collection. Rarely, do people talk about “Counterparts” or “Clay” or “Two Gallants.” Some of the stories in Dubliners are better than others, and if you compare something brilliant, like “Araby,” with something not very good, like “After the Race,” it’s pretty clear that even Joyce struggled with the form.

“After the Race” was one of the first stories Joyce wrote, published in 1904 in The Irish Homestead, and it’s easy to tell. The prose is great, as is to be expected, but there is very little in the way of a narrative or causality. The story doesn’t seem to be much more than an insignificant collection of scenes strung together. (Yes, there is a theme about class and money, but it feels lost in the shuffle.) Worst of all, it fails to showcase Joyce’s finest skills as a writer: human interaction. Whether alone or with others, Joyce’s characters, from Molly Bloom to Gabriel Conroy, spend the majority of their stories talking about important things, and I don’t just mean things like economics and Shakespeare. They are in constant conflict. Every word is a bullet in the larger Alderian power struggle. In Jimmy Doyle, the protagonist of “After the Race,” is little more than a detached observer. But even his consciousness isn’t all that interesting. And what few choices he does make are given to us in summary rather than action:

They drank to Ireland, England, France, Hungary, the United States of America. Jimmy made a speech, a long speech, Villona saying: —Hear! Hear! whenever there was a pause. There was a great clapping of hands when sat down. It must have been a good speech. Farley clapped him on the back and laughed loudly. What jovial fellows! What good company they were!

Now I get that Joyce is trying to show Jimmy’s ignorance, how he can’t see that his own friends think he’s an utter jackass, but Joyce’s over-reliance on summary deadens that effect. Had he had the characters interact in a real, complete scene, the story would be much more significant.

But again, Joyce was a young man then. He wasn’t experimenting: He was learning. And even still, he had already grasped theme and irony better than most veteran writers, but he wasn’t a master of the form. He knew he had more practice ahead of him.

I don’t see many young writers with this kind of awareness, who consciously work on their weaknesses. If you read Dubliners to completion, you can see, in a non-linear fashion, the growth of one of the twentieth century’s greatest artists, from ignorance of form to mastery of it.

#

In our quest for the new and exciting, we have embraced the mediocre and inconsequential. I doubt very much that Hemingway or Fitzgerald, Dostoyevsky or Tolstoy would ever make their prose their only concern. The masters demonstrated through their work that they gave care to plot, character, theme, symbol, conlict, setting–all the the conventions of story. And when they did subvert our expectations, there was a discernable reason, because the old ways weren’t enough to express it.

I too want to subvert the tradition, but I also respect it. There are many fine things we have gained from it, but few people these days are interested in textbook fiction, the kind we study in college classrooms. They seem to think that the ability to analyze a work lessens it, that discerning the truth of it robs it of its glory.

It’s funny. I always thought of myself as a literary revolutionary, someone who would overthrow the order. Yet most of the work I find does it in ways I don’t particularly agree with, from people unaware of what came before them, which seems to make me the old-fashioned traditionalist, but when I think about it, if bad, incomplete stories are what’s trendy, I guess maybe I am part of the revolution–just on the losing side

May 13, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

I went to see Age of Ultron the weekend of its release. And even though I was less than excited to see it (more obligated than anything else), I ended up coming out pretty happy about the eleven dollars I had spent. It wasn’t the best film ever but neither was the first Avengers. In fact, I like the second one slightly more. But in my two-and-a-half hours of viewing, and the subsequent hour or two of thought I gave it, did I ever once feel as though the film presented any philosophical message that I found particularly uncouth. In fact, I took part in a podcast that same day, and it wasn’t even an issue that we broched.

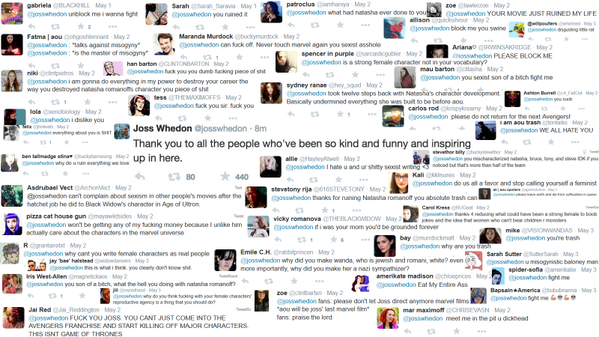

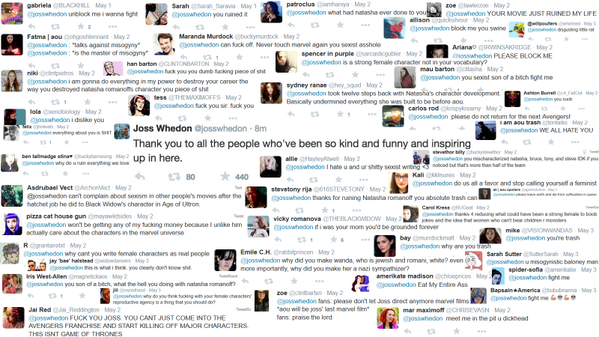

But then along came twitter.

Now whether Whedon left twitter because of these tweets or not isn’t my concern. I’m more so bothered by the pure bile that these people are spewing at an artist whose trying to make something beautiful. And frankly, this is coming from someone who never saw all the fuss over Joss Whedon in the first place. (Yes, I think he has talent: I just don’t think he’s the end all and be all when it comes to witty dialogue.) But why are people so angry? And more importantly, are they right?

Many a spoiler ahead….

One criticism I read came from blastr.com. Two of their critics were discussing Age of Ultron and bemoaned the “forced” relationship between The Hulk and Black Widow. Krystal Clark made the following remark:

“And I’m gonna go there and take a lot of issue with the fact that, in order to make a point for Banner about what being a monster is, they chose to get the one d**n developed female superhero we get in the MCU’s ovaries involved. It’s terrible how Natasha was tinkered with, and a huge decision was taken out of her hands, but wouldn’t it be a lot bolder and more progressive to bypass an antiquated gender bomb like fertility (which, come on, do we even want to touch on that in a superhero tentpole movie?), and just feature a strong, decisive woman like Natasha choosing a super-spy/Avenger life? Because women are so often the girlfriend, wife, mother in every movie out there, you can’t throw in something like a woman not being able to conceive and not have some process it as another thing that Natasha can’t do, instead of focusing on everything she can do.”

This seems to be a problematic analysis of their relationship and the farmhouse scene in general. First, Clark seems to be saying that in order for Banner and Romanov to be able to relate, monster-to-monster, they had to discuss their monstrous details. And according to Clark–and many others–being infurtile is on pare with being a giant green rage monster.

This, I believe, is not the case.

The monstrous side of Black Widow comes not from her inability to have children but from her sins as an assassin, which is shown vaguely in her vision brought on by Scarlet Witch. In order to be a weapon, Black Widow had to be a bad person, had to betray the innocent–much like the Hulk. And that’s the connection, I think, the two make. But when Banner says he can’t have what Hawkeye has (a farmhouse and a wife and three children), Romanov tries to comfort him by saying that she can’t have it either. That’s why it makes sense to jump into a relationship.

Furthermore, Clark asks why does the film have to have this relationship when it could be just Black Widow kicking ass. Now, I know this might sound crazy, but if you spend anytime watching shows or films with bad ass chicks in them, there is often something wrong with that bad ass chick. Just look at a character like Olivia Benson from Law and Order: SVU.

Benson, for a good portion of the series, didn’t get involved in serious relationships. She was a fuck them and leave them kind of woman. Why? Because a woman is tough, she also doesn’t have the ability to love. Of course not, just look at a character like Kima Greggs from The Wire. But that show, unfortunately, is an exception to the rule.

I can think of very few films where a character isn’t involved in a relationship in some way. Look at a movie like Die Hard. John McClane isn’t just a New York cop fighting terrorists: He’s fighting terrorists to save his wife and fix his marriage. But he’s still a bad ass, just a vulnerable bad ass.

How about John Wick? He is defined by his husbandry, devoted to his wife even in death.

All characters worth watching love someone, and Black Widow’s love of the Hulk makes sense. She loves him because he’s not a fighter. It’s something that comes easy to her and everyone around her. She wants someone who’s different. And just because she gave up her ability to have children biologically doesn’t mean she’s a bad woman or a monster. It means she has different priorities. It means she’s happy to be Aunt Nat, not a mother.

And as for Clark’s suggestion that this film turns her in the “girlfriend, wife, mother,” it really doesn’t hold much weight as she seems to get more screen time than Banner. In fact, people are quick to say that she’s become the stereotypical damsel in distress. I guess they missed the twenty minute action sequence where she single-handedly turned the tide of the war against Ultron. I guess they were just supposed to get the Vision back without any trials or tribulations. I guess movies and stories should just be consequence-less.

And of course, who comes to rescue her? Not the Avengers, not even the Hulk, but plain old Bruce Banner. That, I think, says something. It shows growth in his character and hers. He, for once, isn’t the pansy wuss scientist without turning green, and she, for maybe the only time in the series, is vulnerable, needing some help. It doesn’t invalidate her existence. It doesn’t make her weak. It just means she failed–but only for a moment. Once she gets out of her cell, she’s back to ass-kicking. And not only that: She’s saving lives too.

That’s a pretty stark contrast to the woman we see earlier in the film.

Widow goes from someone who takes lives and must carry those sins with her to someone who saves them. That’s why she’s able to go back to the Avengers and work with Captain America to assemble their new squad. She has found meaning in what she’s doing. Sure, she still wants a life with Banner, but it doesn’t define her. This isn’t Bridget Jones’s Diary or Twilight. She’s not that woman who is successful in all avenues except love and feels horrible about it. Those kinds of characters are the worst propaganda as their lives are meaningless without a man. But in Black Widow’s case, it’s icing on the cake. By the movie’s end, she has found some real happiness, even if it is bittersweet.

But of course, if you only spend time analyzing one scene and cherry pick your evidence, I guess it’s easy to complain that a movie is sexist.

April 29, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

Lately, there’s been a lot of talk about the experiences of people of color in MFA programs. First, there was Junot Diaz’s piece at the New Yorker last year. And just recently, David Mura wrote up an essay on Gulf Coast‘s blog. Both of them describe their experiences as people of color in the MFA hegemony, and I have no doubt that their frustration is real. There are a lot of white people in MFA programs, and it can be alienating I’m sure. (We only had one person of color in my MFA cohort and only a handful of professors of color, and I cannot say how they did or did not feel. I did notice that race was rarely discussed but only because it seemed that the white people tended to write about white people and the people of color tended to write about people of color. I did not feel, fortunately, if it was brought up, that it would not be ignored or trivialized.) But in both articles, there seemed to be an underlining idea, one that made me somewhat uncomfortable as an artist. They suggested that writers have a certain responsiblity to depict their reality, which I agree with, but that comes with a caveat: that a writer’s reailty should consider the reality of others.

And this got me thinking.

#

In Mura’s article, “Student of Color in the Typical MFA Program,” he says that a lot of white people are ignorant to this topic of race, unwilling to discuss the ways they consciously and unconsciously uphold white supremacy in their fiction. He writes:

If and when the student of color voices her objections to the piece, more often than not, neither the white professor nor the other white students will respond to the actual critique; nor will they inquire further into why the student of color is making that critique.

They disregard this opportunity to discover their own whiteness, to investigate why a particular character is a stereotype, and potentially, right the problem. I think these are all fine ideas worth exploring. (I am, after all, Italian-American and, therefore, bleed marinara.) But there’s an implicit assumption, if the writing workshop recognizes and discusses and agrees upon this attempt to fix things in their stories, that I find problematic: Artists, with a little help from others, can fully control their message and its effects on the individual reader.

#

A few years ago, I was reading an article in College English by Gay Wilentz. It claimed that The Sun Also Rises was an anti-Semitic work, conveying the nation’s anxiety over the Jewish usurper. The author gave many examples and laid out her case as best she could, but it was something I didn’t buy. The novel seemed so much more complex than that. Sure, there were a lot of characters who hated Robert Cohn because he was Jewish, but I wasn’t sure if the novel necessarily endorsed that type of behavior. After all, Jake Barnes’s opening narration presents Cohn as a somewhat tragic figure. Barnes describes him as “very shy and a thoroughly nice boy,” who “never fought except in the gym.” He even tells us that the reason Cohn took up boxing in the first place is “to counteract the feeling of inferiority and shyness he felt on being treated like a Jew at Princeton.” If the novel is trying paint Cohn as a Jewish stereotype, it doesn’t seem to be very successful. Even later, when Barnes goes fishing with Bill, Bill asks him to say something pitiful. Barnes answers, “Robert Cohn.” That seems to run contrary to this idea of Cohn as the Jewish boogeyman. And furthermore, while the rest of the cast are quick to call Cohn a “kike,” Barnes, as far as I can remember, never utters the word himself. But instead of recognizing these points of contention, the critic ignored them: They weren’t relevant to her data set.

She had an argument, and she was going to prove it.

Most people would ask what was Hemingway’s point? They might even wish to summon the author through séance and ask him his reasoning, but I feel this too wouldn’t be very valuable. Why should we worship Hemingway’s analysis? He’s not God of the text, just the vehicle from which it came out. There’s a complexity there, and it’s not easy to say exactly what it is or is not.

And it’s not just in literature that I see this either. Tyler Shields, a photographer did a photo shoot with Glee cast member Heather Morris.

A few people said that these photos glamorize domestic violence, and the photographer himself later issued an apology. Now let’s actually look at some interpretations of these photographs.

In the first photo, the woman, who has a black eye, is restrained by the iron. She clamps down on the cord to bite it. She is dressed like a 50s housewife. The first way we can perceive the image is that it is a sexualized fantasy, depicting what some wife beaters probably masturbate to. But personally, that’s a little simplistic. She’s restrained because she’s bonded to domesticity, a burden the iron represents. Her husband, most likely, gave her that black eye. But the fact that she’s biting through the cord suggests resistance, the desire for escape. And if we look at the next photo, where she places the iron over the man’s crotch and smiles, there seems to be another message, and that’s one of empowerment. I’m not saying these are the only interpretations. And none are superior. But there does seem to be a problem with saying that because one of these interpretations angers us, that is no longer valuable or useful. It’s art, and it isn’t designed to have a specific, concrete meaning. That’s the beauty of it, the–as the deconstructionists would put–undecidability of it.

So why does the artist need to apologize? Should Shields have foreseen this possible consequence? And if he did, how could he correct it? There’s no doubt a meaning Shields perceives as viewer himself (not that his is the “correct” one). But let’s say someone mentioned this possible interpretation, and he reshoots. Won’t there be another argument against him–somewhere? Isn’t there something which will always rub someone the wrong way?

#

Roland Barthes, in his book Image, Text, Music, wrote: “To give an Author to a text is to impose upon that text a stop clause, to furnish it with a final signification, to close the writing.”

It seems like giving a text a critic does the same thing.

We assume that because the author has summoned the work into existence that he or she is God, but if we fool ourselves into believing this, then there is no further cause for investigation. But if we say that because an interpretation is valid and that interpretation evidences a message we disagree with, then the work must be condemned and extinguished, unworthy of appreciation or discussion.

But I think this too starts with the wrong supposition.

Art is an act of creation, not just on the behalf of the creator, but the individual viewer too. It is an act of two halves of the same soul coming together to create meaning, and that meaning exists uniquely between each reader and each author. If we impose our flawed and cherry-picked readings on all others–and the author–we do all art a disservice.

#

I was so excited my junior year of college. I had known I wanted to be a writer from the moment I failed physics my freshman year, and I was finally getting a chance to take a class in creative writing.

My excitement quickly subsided as I realized that I was the only person who actually wanted a career as an author. Everyone else, it seemed, took the class as an easy elective. Nonetheless, I persisted regardless, scribbling voluminous notes on people’s manuscripts that they tossed in the trash after class.

We spent the first half of the semester writing poetry, and in that time, I wrote two bland poems. One was an image poem; the other was about consumerism–or something like that. They were not very good poems, but I had little interest in writing poetry. I wanted to be a novelist.

I read anything I could get my hands on. I explored the Canon, read as many books off as many great novels lists as I could find, burned through the recent National Book Award and Pulitzer winners (including Diaz’s Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, which I loved). I spent afternoons in the library, and in the evenings, after work, I paged through Wikipedia trying to pick up every bit of literary history there was. I also was particularly fond of Bret Easton Ellis.

One of our first fiction workshops showcased one of my peers and me. I couldn’t wait to learn what the weaknesses were in my writing, places where the pacing sagged, where characters motivations were unclear, where the style could be sharper. I longed to learn the craft, the necessary elements in telling a story. All I had to go on, at that point, was what I picked up from the great fiction I had read and a few articles I had read online. I couldn’t wait to have it all explained by an expert.

I should have known what I was in for after we discussed the first author’s work.

My professor, an academic and poet (I use that term loosely as she has fewer artistic publications than I do and is at least twice my age. One of her poems that I found online told the story of how Oprah was at the foot of her bed and told her to go for a run or something. It was not a worthwhile read.), didn’t focus on the writer’s craft. Instead, she handed out a photocopy of the definition of heterosexism. She said that the writer’s liberal use of the word “faggot” conveyed a heterosexist attitude.

I found myself as the only voice of descent as the rest of the class sat in silence.

It wasn’t long before we moved on to my story, a near twenty page ode to Ellis. There was sex, men who couldn’t orgasm and woman who could, murder for hire, a double-cross, and sex. I do not think the story was well-crafted now, but I was young and immature and still learning as an artist. I had some idea that I was showing how some men may feel in society and how they go to crazy means in order to reassert their masculinity. It was a model of bad behavior that spoke for itself. Instead, my story was accompanied with the definition of misogyny. My professor said my story was inappropriate for class and expressed a hatred for women.

Needless to say, I wasn’t all that happy about it. At first, all I could muster when she asked for my opinion was that I felt like a douche.

However, after I thought about it, I tried to say it was pretty clear that my character was a scumbag, that people shouldn’t be going to the lengths he did, that I didn’t need to spell out what a bad man he was. I even referenced a letter from Chekov, who wrote:

You abuse me for objectivity, calling it indifference to good and evil, lack of ideals and ideas, and so on. You would have me, when I describe horse-stealers, say: “Stealing horses is an evil.” But that has been known for ages without my saying so. Let the jury judge them, it’s my job simply to show what sort of people they are.

But the conversation didn’t make any difference.

When I got my draft back, I learned that she had graded it as well. I “earned” a D-. (Who the fuck grades drafts, anyway?) That, I felt, was pretty unfair. I had written the longest story in the class, one that had a beginning, a middle, and end, one that had dialogue and description (a lot of description). And as far as I could tell, I was the only one who actually took the class seriously!

Her notes didn’t say anything about craft either. She didn’t tell me that acts needed to be shortened, that the plot was non-sensical, that the characters were unrealistic, that the symbolism didn’t work, or the theme wasn’t clear. She focused on the meaning, her meaning.

Of course, I’m not one to take defeat lightly. The first thing I did was appeal the grade to the dean, writing a two page letter on the multitudinous meanings of literature, citing everything I had learned from my theory classes. I gave a list of novels which, at some point in time, were deemed controversial and had graphic, shocking sexual and violent content.

My appeal was dismissed out of hand.

But again, I wasn’t going to roll over, and I did the one thing I could do: I wrote. I wrote a new story for my next workshop, one squarely aimed at my professor’s philosophy, one which would be so carefully written as to prevent any misinterpretation. I was going to be so damn clear and so damn moral that even Jeremy Collier would blush. I told the story of a writer who was attacked quite regularly for his perceived misogyny, who felt he was being misread because he thought of himself as a feminist. (I’ve always been known for my subtlety.) The story contained a plethora of footnotes that gave an overload of information. All profanity was excised, replaced with “[expletive deleted].” The protagonist is a bit of a jerk, but his favorite author is a female feminist poet (the poet part was an attempt to suck up to my professor so I wouldn’t fail), who he talks to early on about something unrelated to the plot. And the climax takes place at a reading, where a radical female feminist stands up to shoot him, but of course, even that violence I neutered. Her gun shot not bullets but a flag that read, “Bang!”

It was not a very good story, but I thought the message was clear: Feminism is good, but radicalism isn’t.

The day of the workshop came, and nobody seemed to have much to say, not even my professor. At the end of class, she handed me back my manuscript, and I searched through and read her notes. She highlighted the climax, where I had added a footnote explaining who my antagonist was and why she was a bad person and how she promoted the wrong brand of feminism, essentially that being a radical separatist was bad.

My professor asked, however, “Why do you want to depict feminists this way?”

#

David Mura and Junot Diaz both teach at a writer’s conference exclusively for writers of color, called The Voices of Our Naton Association. Mura writes:

On a larger level, the student of color in a VONA class doesn’t have to spend time arguing with her classmates about whether racism exists or whether institutions and individuals in our society subscribe to and practice various forms of racial supremacy. Nor does the student have to spend time arguing about the validity of a connection between creative writing and social justice.

And there’s a part of me that agrees with that last bit about creative writing and social justice. I think that artists don’t write exclusively to tell a story: They have a message–and they should. But it doesn’t mean that it’s the only reason they write. It’s a pretty complicated affair, and fiction doesn’t serve just one person. Joyce didn’t like what he saw people doing in Ireland, but that’s not the only reason he wrote what he wrote. He wanted to convey, according to me, consciousness, the subjectivity of experience and perception, the cost of becoming an artist, the paralysis that infected Irish individuals, the beauty of sex, the Irish identity, his disgust with the Church. But he also wanted to write beautifully and tell a story and make people feel things. And he never does so didactically.

I don’t think we can have our cake here and eat it too though. There’s a difference between writing an essay and writing a story. An essay’s meaning is not up for debate, for the most part: It is a reasoned, logical argument. It’s meaning is fixed and can be defended or attacked. Frankly, it’s a better medium for making a point. A story, however, never once commits itself to one idea only. It is not a clear cut argument: It is a collection of evidence that can be interpreted and enjoyed or interpreted and hated.

And we are utterly helpless to control it. It’s that last part that really frustrates everyone else, but I’m OK with that.

I’m not in the business of pleasing others. I don’t write because I want to confirm your biases. I don’t write to make you feel better about yourself. I’m not trying to, as Vonnegut said, open my window and make love to the world because I know I’ll catch cold. Instead, I write to show you the reality I perceive, the world I inhabit.

We are the masters of our own little universes: Critics be damned.

April 25, 2015 / Vito Gulla / 0 Comments

I just started teaching drama to my comp II class, and typically, the first play we do is Glengarry Glen Ross by David Mamet. It’s one of my favorite plays by one of my favorite dramatists. There’s a line that I’m particularly fond of:

The great fucks that you may have had. What do you remember about them[…]? I don’t know. For me, I’m saying what it is, it’s probably not the orgasm. Some broad’s forearm on your neck, something her eyes did. There was a sound she made…or me, lying, in the, I’ll tell you: me lying in bed; the next day she brought me cafe au lait. She gives me a cigarette, my balls feel like concrete.

It’s a great one because it’s so damn true–with anything you’ve ever enjoyed. Those fragments of memories that come streaming through your mind, it’s always one moment, always that one little image, insignificant, divorced from any goal or objective, but for some reason, it stays.

#

When I was on the verge of adolescence, I couldn’t wait until the Christmas of 1998. I must have pestered my mother everyday to get my present early. Most of them could wait, but the one I needed was The Ocarina of Time. Of course, it did little to change the delivery date. I did eventually get it and played from start to finish in a few weeks. It was (and probably still is) the greatest game I have ever played. But at the time, I didn’t know why, didn’t know how to express it. All I knew was that it was different and “fun.”

#

I’ve always been interested in movements, those paradigm shifts for the entirety of art. It’s nice to have those categories, to point to those commonalities of an era. And there always seems to be some figure who is leading the charge. Romanticism had Byron, Keats, and Shelley. Transcendentalism had Emerson and Thoreau. Naturalism had Crane. Modernism had Joyce and Woolf. Post-Modernism was Burroghs and Ginsberg. But what about now? What–really–is pushing us forward? We’re not at a loss for good authors: Junot Diaz, Johnathan Letham, David Eggers, Johnathan Franzen, Jennifer Egan, and this list goes on. They’re all wonderful in their own right. And we still have those legends who creep out from behind the curtain every so often, like Roth or DeLillo or Pynchon. But I don’t see anybody trying to shake things up. Everyone seems to be content with the way things are. It’s been over twenty years since Tom Wolfe said we should move back towards realism, as if that was the only way to capture an era. But nobody seems to want something different, something that is in the moment and also new. To me, the magic of movements isn’t just what they aimed to depict but how.

I guess what I’m asking is, Why aren’t we trying to reinvent ourselves?

#

I once did a Google search for the movement after Post-Modernism. Most were unhelpful. The answer was typically Post-Post-Modernism. It didn’t give an explanation of the movement’s philosophies or goals or what differentiated it from what came before. The closest to a definition I found was a few writers who were thrown under the bus.

But then I saw something that seemed a little more interesting. They called it the New Sincerity.

#

By the time I made it through my first year of undergraduate, I had probably watched more movies than most people watch in a lifetime. I had no interest in becoming a filmmaker because controlling a set and overseeing actors and editors seemed like a lot of work. Not to mention, somebody is going to come along to fuck it up. The less hands on what I’m making, the better.

I guess that’s why I choose writer instead.

But I spent a lot of time thinking about those movies too, about the choices those directors made and why. Little things started to fall into place: the use of shadow, the actor’s placement in the frame, the transition between scenes. I realized that the very good and the very talented didn’t leave things up to chance. They shot something a certain way not because it was cool or looked nice but because it had meaning.

A great movie wasn’t just good craft. That was a given. You had to make sure the acting was good and that the characters were realistic and believable and the dialogue felt true and that the costumes and sets and editing were spot on. Those things, production value, were what it made it easy to watch. But the true geniuses thought more deeply, saw things differently, they needed to convey something.

#

Just recently, my girlfriend was reading some book in bed, something that recieved attention here and there in the papers. I read a few pages over her shoulder, and other than pointless fragments, the book had a good voice and good prose and seemed true and beautiful. It didn’t take me long to recognize what it was though.

I rolled over and shut my eyes, and my girlfriend asked me what I thought.

It’s just what this world needs, I said. Another book about World War II.

#

The thing that bothers me about all the short fiction I read in the magazines is that they never seem to talk about the world I live in. It’s either a sorry account of hipsters trying to find meaning in their world of irony or about some long ago historical event or some academic who spends his or her time trying to bang students and read Proust. Rarely, do I find stories about real people, stories that aren’t preoccupied with rehashing the past.

I guess it’s easy to blame the MFA. It seems like the only people who read the magazines anymore are the MFAs trying to get into them. So I guess it’s about catering to your audience. But I don’t think all of us are that self-involved. I mean, I have an MFA too, but the last thing I want to do is read a story about workshops or seminars or some dickhead who enjoys Derek Walcott–especially when the reference is empty, only an attempt to display how widely the author has read.

I like reading probably more than the next guy, but I would never say it’s the only thing I do. And even though I’m a college professor (adjunct, of course), I certainly wouldn’t say it’s the most exciting part of my day.

When I get together with my friends, we spend a lot of time just talking, maybe have a few drinks, watch a movie, play some video games. We have things we want to do, things that worry us, things we like to do. I think we spend more time on our phones and on the internet than we do a lot of other things. And I don’t think it’s bad either. There’s a lot of great stuff on the internet: There’s Wikipedia and Facebook and Twitter and Imgur and Youtube and YouJizz. It’s a part of our lives now. Sometimes, it seems like the only constant, especially when you have to wonder how you’re going to pay off your student debt on your retail job salary–even though you went to college for medieval history.

#

For as long as I can remember, I wanted to do something great. I wanted to make some kind of discovery, do something that had never been done before. For a time, it was going to be paleontology. By sixth grade, it was end global warming by discovering nuclear fusion. That lasted til college, and I settled on writer.

I guess I’m still pretty naive.

#

Whenever you read a novel that focuses on technology, it seems like the message is always the same: This thing can be dangerous. Emerson probably said it best: “The civilized man has built a coach, but has lost the use of his feet.” I understand the perspective, but I feel it’s far too common. Everyone seems to be a little too glass-half-empty on the subject, and it’s not an idea that seems to be going anywhere anytime soon.

Just look at the new Alex Garland movie, Ex Machina. Now, I have little doubt the film won’t be worthwhile. Garland’s writing is pretty damn good, and I’ve enjoyed everything he’s done with the exception of The Tesseract. But if the trailers are any indication, it seems like we’ll be getting that same old message once again. Of course, I haven’t seen it (though I probably will) and I’m rushing to judgment and maybe it’s just me, but why isn’t anybody saying how awesome this all is?

Instead, people seem to pine for that great yesterday, when things were simpler. There’s the paleo diet. There’s internet blocking software. There’s parent-controlled time limits on iPads. There are people going off the grid.

I don’t know about you, but I like progress.

#

So where do we go from here? I don’t know exactly. This isn’t a manifesto. It’s not a how to guide on the direction we need to take to get out of this rut. If this is anything, I think it’s a push towards something greater. After all, the first step is admitting you have a problem.